#it established an artistic and commercial legacy that has defined her career since then

Text

White Shirt | Research

FASHION PHOTOGRAPHY

Nowadays we take it for granted that fashion photography is an art form as creative and varied as any other, but it wasn't always this way. Over the past 100 years the medium has worked hard to establish itself as a valid and legitimate form of expression, so read on for a thorough history lesson in the movements that defined a genre.

As with all great advertising, some of the most recognizable fashion campaigns in history have become every bit as iconic as the brands they were first designed to sell. Somehow, these great examples manage to capture the spirit, voice and aesthetic of a designer so perfectly that they add a whole new level of context to their brand. Whether it’s the model chosen, the styling of their outfit, the set design of the shoot or the photographer themselves, great campaigns transcend the actual clothing and help tell a story all of their own.

1910 – 1934: Edward Steichen and the Condé Nast years

To many, Edward Steichen is the founding father of modern fashion photography. After a supposed dare by a close friend, Steichen undertook the task of promoting fashion as fine art via the medium of photography. To do this, he took a series of photographs of the gowns created by renowned French fashion designer Paul Poiret, which were subsequently published in the April 1911 issue of Art et Décoration magazine.

Widely considered the very first modern fashion photographs, they conveyed the aesthetics, movement and details of the clothes as central to their approach. His style centred heavily on the model, in typical portraiture style, but used lighting and carefully planned studio setups to focus on the clothes and give them a lavish and elegant look that was indicative of the time.

Another crucial factor in widening the appeal of modern fashion photography came in 1909, when the successful publisher Condé Nast purchased American lifestyle magazine Vogue. In doing so, he created the world’s premier fashion publication — one that gave photographers such as Steichen, Cecil Beaton and Horst P. Horst a platform to showcase their work to a huge new audience. In 1913 he followed that up with the launch of Vanity Fair, and together the two titles spent decades fighting Harper’s Bazaar to become the top fashion magazine in America.

What Steichen and Vogue gave to modern photography were the blueprints for almost all fashion advertising that was to come in the years after. Steichen formed his own unique visual vocabulary throughout the ’20s and ’30s, distilling classic renaissance imagery with cubism and futurism to create something that was fresh and exciting. His use of models, lighting and experimental studio techniques were completely revolutionary and, for many years, his contemporaries had no other choice but to follow his path. His importance cannot be exaggerated; Steichen changed the face of fashion photography, and his innovations are still being used to this day.

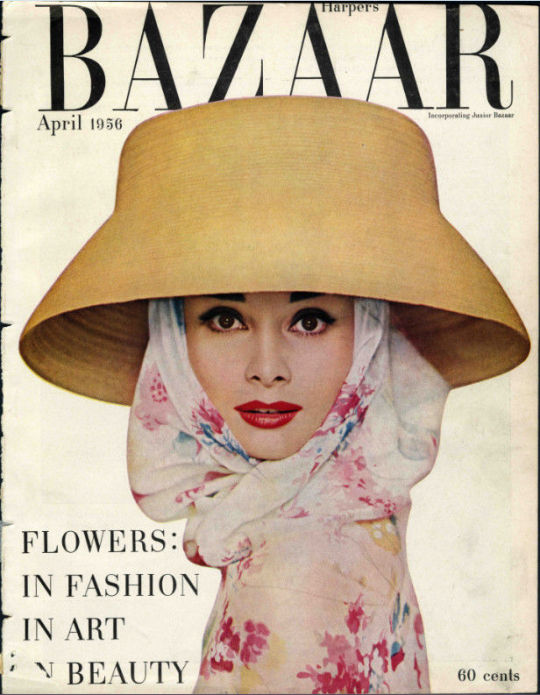

1934 – 1944: The revival of Harper’s Bazaar and The Design Laboratory

For many years, Harper’s Bazaar lacked the edge it needed to compete with the Condé Nast publications. The magazine���s fortunes changed in 1934, however, with the appointment of Russian photographer Alexey Brodovitch to the role of artistic director. With him in place, Harper’s Bazaar started down a new path that would change the landscape of fashion photography forever. He implemented radical layout concepts, used typography in bold new ways and had a vivid approach to imagery. It was his mix of elegance and innovation that transformed the fortunes of Harper’s Bazaar, securing its long-term future.

However, Brodovitch’s influence was more resonant than simply the pages of the magazine. In 1933 he started a course at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art called the “Design Laboratory,” where he taught the full spectrum of modern graphic design principles. In attendance were young photographers such as Irving Penn, Eve Arnold and Richard Avedon. It would be these students that would go on to shape fashion photography on an almost continual basis for decades to come, all helping extend Brodovitch’s legacy long into the future.

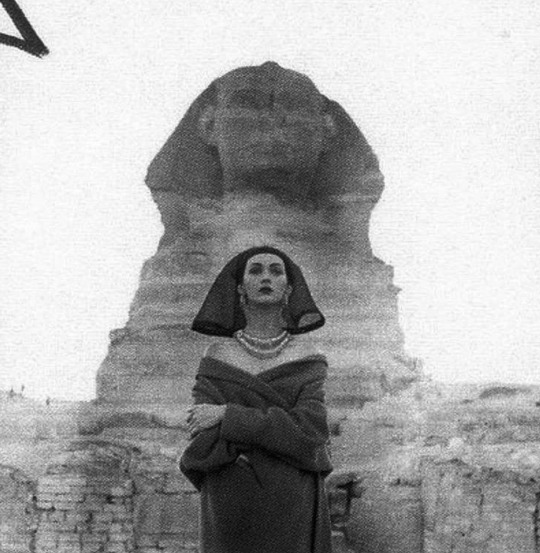

1944 – 1960: Avedon and The Great Outdoors

One of Brodovitch’s early students at the Design Laboratory was Richard Avedon, who started his career in 1944 as an advertising photographer. Avedon quickly found a fan in Brodovitch, who spotted his talent and sent him to Paris in 1946 to cover the latest collections from the premier fashion houses. Young and full of energy, the images Avedon captured for Harper’s Bazaar represented a new direction for fashion photography.

Avedon’s style was all about one thing: movement. He replaced the static, lifeless poses of the Steichen era with photographs full of verve and vitality. He shunned the studio, preferring to work outdoors or on location. Capturing lively street scenes and bustling parties, his models were photographed in the moment, showcasing their natural femininity; the flowing clothes seemed somehow to be an elegant extension of their own bodies.

1960 – 1970: The divide

Avedon’s move to shoot his models in the moment was a real turning point for fashion photography. Those such as David Bailey used this style extensively to capture the new and exciting times of swinging London in the ’60s. Bailey’s photography for British Vogue built on Avedon’s ideas, but gave them an even more youthful feel, while his carefree approach linked model, setting and lifestyle like never before. Prolific photographers of the present day, like Mario Testino, owe a lot to work like this.

But there were some, such as fellow Brodovitch student Irving Penn, who continued to stick to the traditions of the studio. His famous cover for the April 1950 edition of Vogue featured model Jean Patchett in contrasting black and white. With tone and angle set in opposition, the result is dramatic, yet tranquil and this image in particular sums up his approach to fashion photography. Although his style was starting to fall out of favour during the ’60s, Penn changed the face of fashion photography in subtle but far-reaching ways for many years to come.

1970 – 1980: Return to the studio and the rise of sexual controversy

Capturing movement outside the confines of the studio had been the modus operandi of many photographers throughout the ’50s and ’60s. But, by the start of the 70s, a resurgence in studio work was well underway. Taking cues from photographers such as Steichen, Beaton and Penn, this new movement was defined by its use of female nudity, overt sexuality and surrealism.

Once again, Richard Avedon was riding the crest of this new wave. Having signed a deal to move from Harper’s Bazaar to Vogue in 1966, he decided to return to the studio for much of his fashion photography work. Referencing the glamour and freedom of the previous two decades, his shoots for Versace throughout the ’70s and ’80s were inventive and exciting. His trademark use of movement was still present, as was his celebration of vitality and confident female sexuality.

Somewhat contrasting Avedon there was Guy Bourdin, a Parisian who relied on sexual imagery to tell a different story. While his critics say that Bourdin reduced the female body to its most erotic parts, often promoting violent and misogynistic views, his supporters argue that he created his own unique brand of surreal mysticism. His advertising work in the late ’70s (including shoots for luxury footwear brands Charles Jourdan and Roland Pierre) often portrayed woman as weak and controlled — a strict counterpoint to works by contemporaries like Helmut Newton and Avedon. However his imagery is undeniably captivating, and the use of bright colour, staged surrealism and sex has influenced the work of modern fashion photographers like Terry Richardson.

1980 – 2000: The age of rampant commercialism

The ’80s were the start of a brave new frontier for fashion photography. Commercialism, a force that had laid somewhat dormant for much of the previous 60 years, suddenly reared its head. Fashion was starting to have a broader appeal as Europe and America’s burgeoning middle class took more of an interest in what they wore. They had more money to spend, and savvy fashion labels like Calvin Klein, Levi’s and Ralph Lauren were only too happy to take it.

A standout campaign from 1981 featuring a 15-year-old Brooke Shields personified this perfectly. Shot by the omnipresent Richard Avedon, the ad for Calvin Klein jeans saw Shields proudly declare that nothing came between her and her Calvins. It was a line that came straight out of an ad man’s notepad, but it caught the public’s attention. Almost overnight it made Calvin Klein jeans a highly desired product.

One man completely at home in the studio, and finding a new demand for his work, was Irving Penn. Throughout the late ’80s he teamed up with Japanese designer Issey Miyake for a compelling and ground-breaking set of adverting campaigns. Taking influence from Steichen’s simplistic approach and blending in his own subtle surreal tones, Penn took Miyake’s futuristic designs and exaggerated them with large, embellished silhouettes, using the pattern of the fabric and the contortion of the human body to showcase Miyake’s creations in a whole new light.

Penn was extrapolating Steichen’s blueprints, pushing the relationship between product, model and photographer further than anyone had done before. He had stayed true to the studio, even when his peers were shunning it. He had used this time wisely and was advanced in his use of lighting and considerate in the sparseness of his shots. This approach has since inspired a whole new generation of fashion photographers to look beyond the normal and push the boundaries of what can be achieved, conceptually, in the studio.

The ’90s produced a slew of classic ads. From the strong female role models portrayed by Donna Karen, to the American dream represented by Ralph Lauren, the ’90s were seen by many as the golden age of the ad campaign. Alongside sex, labels used supermodels to focus their campaigns around, finding an obvious link between their natural beauty and aspirational products.

Once again, Calvin Klein was at the forefront of this new movement, and turned up the heat in a particularly famous campaign from 1992. Featuring Mark Wahlberg paired with a fresh-faced Kate Moss, the unassuming black-and-white shoot by Bruce Weber captured the essence of this new direction. The simple image of them both, topless, sporting clearly branded underwear was all that was needed to get the message across. And it worked. Calvin Klein saw a huge uplift in sales, turning them into a globally recognised brand.

2000s: Hypersexuality

As mankind has thoroughly established over the decades, sex sells. But, while people like Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin had used imagery for its sex appeal extensively in the ’70s, the 2000s ushered in a new age of hyper sexuality that was designed as much to shock as it was to sell clothes.

One man not afraid of using flesh to push his products was Tom Ford. The iconic campaign for his first fragrance, For Men, was shot by Terry Richardson in 2007 and blended Ford’s penchant of sexual imagery with Richardson’s stark and instantly identifiable flashbulb aesthetic. Bourdin was clearly a huge influence on this work; the highly manipulated studio shots, use of colour and slightly sinister portrayal of female sexuality are all present. Strategic placement of the perfume bottle leaves little to the imagination, and the campaign caused a lot of controversy, as well as a lot of exposure, for Ford.

Another campaign from the Tom Ford stable was released in 2003 whilst the designer was working for Gucci. Stylised and simplistic, this ad, shot by Mario Testino, garnered a lot of attention as it featured a female model with the Gucci “G” shaved into her pubic hair. Less about the clothing and more about the preening, it was a bold move for Ford, but one that once again proved the old adage that there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

Although not averse to using sexual imagery in his advertising, Marc Jacobs strode a different path in the 2000s alongside longtime collaborator Juergen Teller. Teller’s distinctive photography style played a huge part in Jacobs’ promotional campaigns and differed hugely from the glamorous, highly stylised shoots of his contemporaries.

One standout example from 2003 featured Hollywood actress Winona Ryder. Having recently been arrested for shoplifting from the Saks department store in Beverly Hills, Ryder arrived in court wearing a Marc Jacobs dress. Spotting an opportunity, Jacobs hired her, and the now infamous ensuing photoshoot encapsulates his irreverent take on design with a devil may care attitude.

Celebrity endorsements and the celebration of wealth

Since Mark Wahlberg first posed for Calvin Klein back in 1992, big brands have been acutely aware of the attention a celebrity can bring to their campaigns. Strong females are a particular favourite, with fashion houses holding their rebellious and provocative spirit in high regard. Miley Cyrus for Marc Jacobs (much to the disapproval of Juergen Teller, who allegedly refused to work with the star), Lady Gaga for Versace and Lindsay Lohan for Miu Miu have all followed in the footsteps of Winona Ryder.

Current campaigns have also an increasing return to the nostalgia-tinged glamour of choreographed black-and-white shots. Hedi Slimane has repeatedly channelled ’70s era Helmut Newton for a large number of his campaigns for Saint Laurent, while Julia Roberts for Givenchy, Madonna for Versace and Mila Kunis for Miss Dior have all featured a similar monotone theme.

Perhaps the most dramatic shift in modern fashion photography, however, is the way in which campaigns are now being consumed. Between 2006 and 2013, the amount of pages dedicated per year to advertising in Vogue fell by 16%. In an age of Instagram and blogs, it’s clear fashion marketers have adopted a new strategy — one that includes a tacit acceptance that images may not ever make it anywhere near a glossy A4 magazine page, and may only ever be consumed on a scrolling social media feed. Content today is created in order to be shared, liked and retweeted. For many brands, lookbooks are the new ad campaigns — cheaper to produce, easier to consume and better suited for distribution across digital mediums.

Once the gatekeepers of the industry, today fashion magazines have been usurped by the internet. For some, this move is democratising, removing the elitism that the fashion industry old guard have long been accused of fostering. But, to many, it is the gentle dumbing down of a once proud art form that, thanks to the work of people like Steichen, Avedon, Newton and Penn, has long held great cultural and historical significance.

TYPES OF FASHION PHOTOGRAPHY

1. Catalog Photography

Catalog photography is perhaps the simplest of the 4 fashion photography styles. Its purpose is to sell clothing, and the focus is on the outfit. It is often a good place to start in the field of fashion photography before progressing to some of the other styles.

Catalog photography really is a type of product photography. The only real difference between catalog photography and product photography is the presence of the model. Even so, the focus remains on the clothes.

The background of the photos are usually plain–white and grey colors are the most common. There are minimal accessories and few props. The models typically stand up straight to show the outfit, although they may strike different poses to show off features of the outfit like pockets.

Usually, the biggest problem the photographer faces with this style of fashion photography is the lighting. You want to use lighting that captures the details of the clothing without washing out the colors. To do this, it’s best to avoid using indoor lights or shooting at night.

2.High Fashion Photography

High fashion is something people see frequently on the cover of their favorite magazines. But, from the photographer’s perspective, high fashion means well-known supermodels in often exaggerated poses, a sometimes unrealistic wardrobe, and all elements including hairstyles and location blended to create a flawless image.

But, getting that flawless image is quite the challenge. You’re constantly confronted with difficult decisions regarding location, lighting, models, wardrobe, hair, and much more. Even if much of that is decided for you, you still have to put it together so that it looks glamorous and appealing.

One of the first things you should do is carefully consider the mood you want to create with the shoot. You don’t have to be too specific and you don’t have to stick with it if inspiration leads you elsewhere, but it’s a good place to start.

You also need the right model for your shoot. You want someone experienced, but also someone who will collaborate with you to create that mood you want. As well as the model, you’ll want a good team.

You’ll want people who are responsible as well as talented. You’ll want professionals in makeup, wardrobe, and hair styling. It also helps if they share your vision for the shoot and the art of photography in general.

If you have a choice of location, you’ll want to again consider the mood you’re trying to create. There are also practical considerations, such as whether you need a permit for your location, and if it’s indoors, you might need permission.

And, then there’s the equipment. You’re going to need lighting equipment as well as a good camera. You’ll want a small weight camera with a good battery life and features that help with low light conditions. You will also want a selection of lenses for varied types of images.

3.Street Fashion Photography

Street fashion, also known as urban fashion, is often thought of as the opposite of high fashion. An offshoot of street fashion is alternative fashion–grunge and hip-hop are examples that later became mainstream street fashion styles.

Street fashion looks are more rugged than high fashion. It consists of the kinds of things people wear everyday like jeans, shirts, and hoodies. It also includes dresses that look elegant, but don’t sacrifice comfort.

Photographers who specialize in this style are often shooting regular people on the street rather than models. But, you’ve got to be careful about getting permission to photograph people on the street. The rules aren’t always clear, as several street fashion photographers can tell you.

Most of the time with street fashion, it isn’t just about what the person is wearing; it’s also about their expression, how confident they look, the light, and how what they’re wearing accents their attitude.

To capture street fashion shots, most photographers use a longer lens. That way, they can get photos from a distance without making people feel self-conscious about the shoot.

4 Editorial Fashion Photography

This is fashion photography that tells a story. You’ll find editorial fashion photography in publications like magazines and newspapers. The images usually accompany text, which can be about a wide variety of subjects.

Editorial fashion photographs can also tell the story themselves or they may suggest an intriguing backstory. Often you’ll find editorial fashion images that are part of a theme or concept, or they may relate to a particular designer or model.

The goal here is to create a specific mood that tells the story. These images might involve one brand or several brands and various styles of photographs, from closeups to long distance shots.

That means there are likely to be various types of shots requiring different equipment as well as different makeup, wardrobe, and hairstyles on your models. There are also likely to be a number of different props.

Despite the challenges, editorial photography can be one of the more rewarding fashion photography styles because of the creativity it allows.

If you’re considering fashion photography as a genre, these 4 styles can give you an idea of the different possibilities in the field. Of course, you’ll need to get the proper equipment as you would with any genre, but once you have that, there are a number of styles from which you can choose. Really, it’s about deciding which style fits your particular needs and desires.

0 notes

Text

VLK Architects Announces New Executive Leadership Structure

VLK Architects proudly announces a new executive leadership structure to support the firm’s continued investment in providing exceptional work opportunities for its employees while providing extraordinary client service and innovative project solutions. Sloan Harris AIA, NCARB, LEED® AP has been named as Chief Executive Officer; Justin Hiles AIA, LEED® AP BD+C, Chief Operations Officer; Ken Hutchens, Chief Creative Officer; and Linsy Grozdanich, Chief Financial Officer. This new leadership structure is a natural progression in growth for the firm and will position additional leaders who are experts in their chosen areas to be more focused, timely, and strategic in their decision-making. “VLK is all about being client-responsive,” said Sloan Harris, VLK CEO/Partner. Having a formal executive leadership team that can make decisions on behalf of the firm is a true benefit to our clients.”

Sloan Harris AIA, NCARB, LEED® AP – Chief Executive Officer

As Chief Executive Officer, Harris reports to and advises the Board of Directors for firm performance and operations. He is responsible for high-level strategic decisions and the firm’s overall growth, setting the tone, vision, and culture of VLK while working with other firm executives and leaders for input on significant firm decisions. Sloan’s vision for the future, enthusiasm for building great communities, and innovative leadership represents VLK Architects’ commitment to delivering exceptional architectural services. Since he joined VLK Architects in 2003, Sloan Harris has been a driving force in the expansion of the markets served by the firm. As a Partner, Sloan manages the firm’s client services and actively engages with not only the owner but also consultants and internal staff to achieve the client’s vision. In addition, he directs VLK’s business development pursuits. In 2012, Sloan was promoted to Principal at VLK. In 2015, Sloan was named Partner with oversight of business growth strategies, operations, and client management while directing multiple signature projects such as the Arlington ISD Dipert Career and Technology Center, iProspect’s headquarters, Allen ISD STEAM Center, and PMG’s headquarters. Sloan leads the firm’s market sector pursuits in commercial and institutional projects, including corporate interiors, mixed-use, automotive, K-12, and higher education. Sloan’s leadership has contributed significantly to VLK’s remarkable upward trajectory and elevated visibility in the marketplace. With a Bachelor of Science in Architecture, a Master of Architecture, and a Master of Business Administration from the University of Texas in Arlington, Sloan is NCARB-certified, and a LEED® Accredited Professional. In 2011, he was honored as a “40 Under 40” by the Fort Worth Business Press. Sloan’s active participation in civic and professional organizations in Texas proves he is not only a leader for the firm but also for the communities it serves. He is an alumnus of Leadership Fort Worth’s Class of 2012 and is a member of the American Institute of Architects, Fort Worth Chapter, and the Construction Specifications Institute. He has also served on the City of Fort Worth Planning Commission (2014-2017) and as a board member for the Real Estate Council of Greater Fort Worth, the Texas Transit Alliance, and the Cultural District Alliance. “Sloan’s greatest attribute is his ability to set a clear vision and strategy for the firm that allows our enormously talented staff to align around and implement consistently,” said Leesa Vardeman, VLK Principal. Through his extraordinary vision, VLK has experienced unprecedented growth in revenue, number of offices, number of employees, market sectors, and range of services provided. This restructuring will serve to amplify the execution of his strategy by delivering for clear, consistent communication throughout our organization and to enhance the culture that has defined us.”

Justin S. Hiles, AIA, LEED® AP BD+C - Chief Operations Officer

As Chief Operations Officer, Hiles is responsible for the overall architecture operations and performance of the firm, providing management, vision, and leadership to ensure proper operational controls and systems for the benefit of the firm’s architectural practice and firm performance. With 18 years of architectural experience and an extensive background in commercial and educational design, Justin Hiles has served the firm as Project Architect for many of VLK’s most notable projects such as Eagle Mountain - Saginaw ISD’s Sarah Hollenstein Career and Technology Center and Denton ISD’s Dr. Ray Braswell High School, as well as Project Director on Arlington ISD’s Dan Dipert Career and Technical Center and Katy ISD’s Legacy Stadium. Since 2015, Justin has been in the Architecture Director role and has managed the daily operations of VLK’s architectural unit in both Fort Worth and Dallas. He has been directly responsible for implementing strategies and procedures, ensuring the quality of VLK’s designs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Architecture degree and a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Texas at Arlington. He is a member of the American Institute of Architecture (AIA), including acting as the current President of AIA Fort Worth. He has also earned certifications through the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) and is a LEED Accredited Professional and is a member of the Association for Learning Environments (A4LE), DFW Chapter and the Texas Society of Architects. “Justin has been a key factor in ensuring that the performance of VLK on behalf of our projects and clients has been at the highest level. He has also implemented many of VLK’s continuing education for VLK’s architectural practice and procedures,” said Sloan Harris, VLK CEO/Partner. “Justin has truly established himself as a leader within the firm and is a natural fit for the position of COO.”

Ken Hutchens- Chief Creative Officer

As Chief Creative Officer, Hutchens is responsible for VLK’s brand, including marketing and media. Working collaboratively with other creative leaders, developing processes for output of design deliverables, Ken directs the firm’s innovative development of artistic design strategy. Throughout his 17 years at VLK, Ken’s leadership has represented his steadfast dedication to successfully translating client goals into innovative and thoughtful environments. For more than 30 years, Ken has completed a wide variety of project types. As VLK Principal, Ken maintained relationships with long term clients such as College Station ISD, Clear Creek ISD, and Cypress-Fairbanks ISD. In 2015, Ken transitioned to Principal of Creative for the entire firm and has been responsible for driving VLK’s design philosophy. During this time, he was the creator of VLK’s key research, development, and design philosophies and implemented processes that VLK uses today such as VLK | Launch, VLK | Edge, and VLK | Link. With a Bachelor's in Architecture from Texas Tech University, he is a member of the Association of Learning Environments (A4LE), Gulf Coast Chapter, and serves on the Texas Leadership Center’s board of directors for the Texas Association of School Administrators (TASA). “Ken is a high-level thinker, conceiving many of VLK’s unique design approach methodologies. Whether it be overall firm practice and philosophy, branding of the firm or how we approach project design, there is no denying the impact that Ken Hutchens has had on our firm,” said Sloan Harris, VLK CEO/Partner. “Providing him the opportunity to utilize those skills at a C-level leadership position will undoubtedly elevate our practice and our work.”

Linsy Grozdanich- Chief Financial Officer

As Chief Financial Officer, Linsy is responsible for VLK’s Business Departments which includes accounting, finance, human resources, and facilities operations. In addition, she manages financial forecasting processes, reporting, and provides recommendations on long-term business and financial strategy for the firm. Linsy joined VLK in 1998, she advanced through the organization taking on the responsibility of managing the firm’s entire business function through her previous roles as Accounting Manager and Business Director. In her recent Business Director role, in addition to her business and financial responsibilities, she expanded her leadership responsibilities into facilities operations and human resources for the firm. She has a Bachelor of Business Administration in Accounting from the University of Texas at Arlington. “Moving Linsy to the CFO role for the firm will allow her to add essential staff to handle accounting functions and puts her in a position to provide strategic financial advisement to the firm’s leadership on key decisions that steer the direction of the firm,” said Sloan Harris, VLK CEO/Partner. “Linsy is an expert at providing insight regarding financial data and analytics, as well as forward-thinking strategies in regard to the firm’s performance. Every decision made at VLK is for one purpose; to provide exceptional opportunities for our employees to pursue their passion for architecture and to expand on our ability to provide exceptional client service and innovative solutions for our clients. This new executive leadership structure is another step in that direction. I look forward to seeing how our firm continues to grow, create, and innovate!”

from VLK Architects https://vlkarchitects.com/insights/vlk-architects-announces-new-executive-leadership-structure

0 notes

Text

15 Reasons Why “Batman & Robin” Isn’t the Worst Movie Ever

By any reasonable standard, “Batman & Robin” is not a good movie. Joel Schumacher’s film suffers from a multitude of bizarre choices that pull it in a thousand different directions at once. In 1997, both critics and comic fans savaged the film for being a feature length toy commercial defined by campy performances and an incoherent tone. After two decades of continued mockery, the movie’s reputation has rotted even more, and the film is widely considered one of the worst movies ever made.

RELATED: Digital Justice: 15 DC Comics Video Games You Forgot Existed

With “The Lego Batman Movie” weeks away from release at the time of writing this, it’s a perfect time to revisit the older toy-friendly Batman movie. Now, CBR is taking a look back at 15 reasons why “Batman & Robin” isn’t the worst movie ever. Although the film remains deeply flawed, it’s a fascinating production that reveals some truly redeeming qualities upon closer reexamination.

THE SPIRIT OF “BATMAN ‘66”

In the 1990s, Batman occupied a different place in pop culture than he does today. In the wake of the 1960s’ “Batman” show, the character had been primarily considered a children’s character for decades. By the 1990s, Batman had just started to step out of that show’s shadow thanks to the works of creators like Frank Miller, Paul Dini and Tim Burton. Instead of shunning it, “Batman & Robin” whole-heartedly embraced the legacy of the Adam West era and tried to update it for modern audiences.

While that move backfired spectacularly, lighter takes on the Batman franchise have become more accepted since 1997. In recent years, DC Comics has reclaimed the legacy of the 1960s’ “Batman” with comics like “Batman ‘66” and the animated film “Batman: Return of the Caped Crusaders.” Like “Batman & Robin,” these newer projects are filled with tilted Dutch angles and corny jokes. Although darkness still largely defines the modern Batman franchise, “Batman & Robin” reclaimed a perfectly valid version of the characters years before anything else did.

UMA AND ARNOLD

One of “Batman’s” most notable features was its cast of over-the-top Technicolor villains. “Batman & Robin’s” main antagonists are perfectly logical extensions of that era’s campy foes. Uma Thurman’s Poison Ivy channels Mae West, Julie Newmar and Cruella de Vil in a performance that relishes every bad gardening pun. Since Ivy was created by Robert Kanigher and Sheldon Moldoff in 1966’s “Batman” #181, that era’s aesthetics are a foundational part of her character. Although Ivy never appeared in the old show, Thurman’s Ivy would’ve been right at home facing down Adam West and Burt Ward’s Dynamic Duo.

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s turn as Mr. Freeze is one of the film’s most reviled aspects, but it’s a faithful update of the Mr. Freeze of the 1960s. In his three appearances on “Batman,” Mr. Freeze was portrayed as a heavily-accented, pun-loving villain by George Saunders, Otto Preminger and Eli Wallach. Schwarzenegger’s Freeze has the exact same traits with his TV predecessors. Even as Mr. Freeze tries to freeze Gotham City, Arnold’s good-natured, jokey performance keeps the character from ever becoming truly evil, which enables his redemption by the movie’s end.

HEART OF ICE

While “Batman & Robin’s” Mr. Freeze is largely an extension of his 1960s persona, the film recognizes that “Batman: The Animated Series” added a deeper dimension to the character. In the Emmy Award-winning episode “Heart of Ice,” Paul Dini and Bruce Timm gave Mr. Freeze a tragic origin involving his attempts to cure his terminally ill wife Nora Fries. That’s a compelling motivation for any interpretation of Mr. Freeze, even Schwarzenegger’s neon-blue decathlete.

Schumacher and scriptwriter Akiva Goldsman wisely incorporate Victor Fries’ attempts to cure Nora into “Batman & Robin.” While it doesn’t totally work here, the movie replicates a moving “Heart of Ice” sequence where an imprisoned Mr. Freeze stares longingly at a snow globe that reminds him of Nora. By injecting this pathos into Freeze, the filmmakers make him a sympathetic figure who realistically seems like he would help cure a terminally ill Alfred from the same disease that took his wife.

ALFRED’S STORY

After appearing in two Tim Burton directed Batman movies and Joel Schumacher’s “Batman Forever,” Michael Gough’s Alfred is tasked with carrying a lot of “Batman & Robin’s” emotional heft. While Gough had a fairly distinguished career as an actor, his Alfred was largely a supporting character in his first three Bat-film appearances. In this film, Alfred’s sudden terminal diagnosis becomes the driving force behind Batman’s emotional journey towards accepting his place among his adopted family.

While this subplot doesn’t have the space to cohere into something really substantial, Gough elevates the script with the warmth and tenderness that his Alfred shows Bruce Wayne. Although Christopher Nolan’s “Dark Knight” trilogy doesn’t share much with “Batman & Robin,” this film sets a precedent for foregrounding the Bruce/Alfred relationship. While those later films would explore their dynamic to great effect, this film uses that same familial warmth to fast-track Alicia Silverstone’s Barbara Wilson, Alfred’s niece, into the Bat-family.

BATGIRL’S PRESENCE

Despite its faults, “Batman & Robin” contains the only live-action feature film appearance of Batgirl. Although Yvonne Craig’s Batgirl joined Adam West and Burt Ward’s Dynamic Duo after their big screen adventure, the character’s inclusion here is another nod to the 1960s “Batman” series. In the ’60s series and that era’s comics, Batgirl is secretly Barbara Gordon, the daughter of Commissioner Gordon. Since the elder Gordon hardly has a presence in this movie, Batgirl’s familial relationship to Alfred makes more sense in the context of the film.

Although she doesn’t share a last name with Barbara Gordon, Silverstone’s Barbara Wilson shares her aptitudes for computers and motorcycles. While she doesn’t get much screen time in-costume, the film treats Batgirl as an equal to Batman and Robin and gives her a pivotal role in the film’s climax. While Batgirl seems like a fairly likely candidate to show up in the upcoming “Gotham City Sirens,” “Batman & Robin” remains one of Batgirl’s most visible appearances outside of comics right now.

GOTHAM CITY RACER

In one of the film’s better action sequences, Silverstone’s Barbara and Chris O’Donnell’s Dick Grayson race each other through the streets of Gotham City in an underground motorcycle race. Within the context of the film, the event gives Barbara and Dick a chance to establish a kinship over their shared love of thrill-seeking.

In the race sequence, the film’s various tones coalesce into a stylistic delight. The crowded scenes that set-up the race feature several explicit references to films like “Mad Max” and “A Clockwork Orange,” and even an inexplicable cameo from the rapper Coolio. In a strange but inspired choice, the race plays out like a real-life level of “Mario Kart,” complete with balloons and explosions littering the track. Set against the pulse-pounding beat of Underworld’s minor techno classic “Moaner,” this sequence is legitimately thrilling. While the rest of the film struggles to find the right balance between campy comedy and serious action, this scene finds the perfect tonal blend.

BATMAN & ROBIN: THE ALBUM

While “Batman & Robin” was only a moderate commercial success, the album featuring “music from and inspired by” the movie was a smash hit, filled with an eclectic mix of artists. In 1997, the album produced several chart-making singles across genres. The album’s lead single was the Smashing Pumpkins’ “The End is the Beginning of the End,” a frantic mix of distorted guitars and electronica that won a Grammy in 1998. The compilation also featured R. Kelly’s “Gotham City,” a bizarre ballad that ends with a children’s choir praising Batman’s hometown as an inspirational “city of peace.” In addition to Underworld, the album produced memorable singles from rappers Bone-Thugs-N-Harmony, singer-songwriter Jewel and pop-rockers the Goo Goo Dolls.

Although Elliot Goldenthal’s score never reaches the heights of Danny Elfman’s seminal scores for Tim Burton’s Batman films, insertions of his bombastic theme are subtly woven throughout the film. While this might seem like a minor note, it adds a sliver of cohesion to the film’s tonal inconsistencies.

ROBIN’S ARC

The film’s puzzling plot seems to pull most of its characters in wildly divergent directions amidst changing motivations and shifting alliances. While he’s underserved in this overcrowded feature, Robin’s character arc has a clear trajectory that’s true to his comic roots. After being introduced in “Batman Forever,” O’Donnell’s older Robin expresses the same exasperation with being Batman’s sidekick that fueled Dick Grayson’s evolution into Nightwing in the comics.

While Schumacher’s Robin is called Dick Grayson, his quick temper, endless frustration and recklessness seem to be borrowed from the comics’ second Robin, Jason Todd. “Batman & Robin” is only this Robin’s second adventure, and recasting Grayson’s desire to move beyond the Robin identity as an extension of his Todd-esque immaturity works. Since Robin’s emotional arc encourages him to outgrow those emotions, it conveniently paves the way for a return to the status quo at the film’s conclusion. Instead of flying solo, this Robin reaffirms his status as a more equal partner to Batman and Batgirl.

BATMAN IS BATMAN

When this film was released, George Clooney’s turn as Batman was criticized for making the character supremely arrogant and intensely unlikable. Even though decades of stories have conditioned readers and fans to think otherwise, that’s not an invalid interpretation of the character. In the franchise’s most beloved iterations, Batman remains a regular source of frustration to his closest allies. Since most stories cast Batman as a protagonist, these unlikable failings can be easily glazed over in favor of showing Batman doing something cool.

As 2014’s “The Lego Movie” proved, an unlikable Batman can still star in a compelling story. Given Batman’s fundamentally altruistic mission, the interpersonal flaws enrich the character. While Clooney’s Batman seems uncaring, he spends a great deal of time rescuing civilians and thawing out frozen civilians. While some more recent superhero films have featured wanton destruction and loss of life, Batman repeatedly goes out of his way to save Gotham and protect its citizens from danger. Regardless of any other factors, that concern for the well-being of others cements the validity of Clooney’s Batman.

IVY’S POISONS

Despite Thurman’s delightfully exaggerated performance, Poison Ivy never really comes into her own as a multi-faceted character. Although she plays an increasingly less important role as the plot progresses, the script finds some clever ways to tie her into some of its more outlandish aspects. Before she’s doused with plant chemicals and becomes Ivy, Dr. Pamela Isley is seen doing research cross-breeding animal and plant DNA. While the full extent of this Ivy’s control over plant life is nebulous, these experiments explain how she can facilitate the growth of sentient monster plants so quickly.

Brilliantly, “Batman & Robin” also gives Ivy a role in the creation of Bane. As part of her experimental research, Ivy inadvertently creates the Venom serum. While Bane is reduced from a criminal mastermind to a gurgling plant monster, he is given super-strength from Venom just like his comic counterpart. Even if Bane is used as Ivy’s glorified henchman, the revelation of her involvement in his creation ties the characters together well.

JOHN GLOVER’S JASON WOODRUE

A few years before John Glover started his lengthy tenure as Lionel Luthor on “Smallville,” he played a small but essential role as Jason Woodrue in “Batman & Robin.” In comics, Woodrue, also known as the Floronic Man, has had a fascinating trajectory from a minor plant-based DC villain to a mystical “Swamp Thing” antagonist. While Woodrue is only a human here, he plays the mad scientist who’s in charge of Pamela Isley’s research lab and is responsible for her evolution into Poison Ivy and the creation of Bane.

In a sequence that would be right at home in the “Batman” TV show, Woodrue tries to sell the Venom serum to a group of dictators called the “Un-United Nations.” As the character, Glover seems to channel every B-movie mad scientist cliché there is with extreme gusto. Glover hones in on the maniacal glee at this movie’s core and embodies it perfectly during his brief time on screen.

BATMAN LORE

Even though this overstuffed movie barely has enough room for all of its characters, the film is still filled with a number of allusions to Batman lore. Although “Batman & Robin’s” Bane only has surface connections to the Bane of comics, the character’s inclusion here is still noteworthy. When the movie was released, the character had only been around for four years after his 1993 comic debut. Along with the inclusion of a Nightwing-inspired Robin costume and the “Heart of Ice” references, the film showed a remarkable willingness to engage with that era’s Batman mythology.

The film also includes several nods to older, more obscure Batman lore. Wilfred Pennyworth, Alfred’s rarely seen older brother, earns a mention in the film. When Batman���s recounting Mr. Freeze’s origin through the Bat-Computer, there’s a subtle reference to the villain’s original moniker Mr. Zero. The producers of the 1960s’ “Batman” series changed the character’s name to Mr. Freeze for an episode that involved a diamond robbery. The movie references that specific episode by making diamonds the source behind Freeze’s power suit, ice gun and giant freeze ray.

FLASHES OF BRILLIANCE

Despite the tonal confusion that plagues so much of the film, Schumacher and the production team manage to capture a few striking moments of brilliance from the midst of the film’s madness. In one blink-and-miss-it scene, an extreme close up on Poison Ivy’s toxin-filled lips highlights their neon hue and reframes them in the same way a documentary might showcase a poisonous tropical plant.

While some of “Batman & Robin’s” action scenes are very silly, most of the chase sequences work pretty well. In the middle of a chase with Mr. Freeze’s gang, Batman cuts power to the Redbird, Robin’s motorcycle. As Batman continues pursuit, Robin is left to cry out in agony on the fingertip of a skyscraper-sized statue. O’Donnell lets out a scream that releases years of unseen frustration in one of the movie’s best pieces of acting. Having already seen Robin’s exhilaration during the motorcycle street race, the audience is left to linger on Batman’s cruel indifference to his partner’s wants as the chase continues.

GOTHAM CITY

The Gotham City of Tim Burton’s Batman movies was a dense gothic urban environment, shrouded in perpetual dusk. In “Batman & Robin,” Schumacher’s Gotham, brought to life by production designer Barbara Ling, is filled with neon lights and garish color that seems to expand infinitely upwards. With dense pockets of buildings and elevated roads, the city seems to be built around giant figures that look like giant Renaissance era statues come to life and then trapped in steel.

While these design choices are deeply impractical, they bring a hint of operatic grandness to the fundamentally silly proceedings. The cavernous Batcave seems to reduce everything but the Batmobile into miniature size and the Gotham Observatory sits in the palms of a giant statue that towers over the city’s skyscrapers. Schumaker’s Arkham Asylum twists like a whimsical dungeon pulled from a hallucinogenic-fueled nightmare. Where most modern depictions of Gotham have some basis in reality, “Batman & Robin’s” Gotham boldly highlights the inherent unreality of a world with superheroes.

IT HAD TO HAPPEN

Despite its multitude of flaws, “Batman & Robin” was a necessary growing pain in the development of the superhero movie as a viable genre. The failure of this fascinating experiment killed the idea of campy superheroes on film and made it clear that the next wave superhero movies couldn’t just be live-action Saturday morning cartoons.

In the decades following “Batman & Robin,” filmmakers learned from its mistakes and, from its ashes, created the modern superhero film as we know it. These revelations led to a greater emphasis on the sci-fi elements of the X-Men franchise in the early 2000s. As the general public grew more accepting of superheroes, Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy and the early Marvel Studios movies found a streamlined story-driven approach to embrace full-fledged superheroics. The failure of a supposedly kid-friendly Batman paved the way for Christopher Nolan’s adult-skewing “Dark Knight” trilogy in the 2000s and Zack Snyder’s even darker take on the character in the 2010s. While “Batman & Robin” remains defined by misguided choices and tonal inconsistency, it’s never dull and hints at the future highs that awaited the resilient Batman franchise.

Stay tuned to CBR for the latest on “The Lego Batman Movie” and the Dark Knight’s continuing adventures! Let us know what your favorite Batman movie is in the comments below!

The post 15 Reasons Why “Batman & Robin” Isn’t the Worst Movie Ever appeared first on CBR.com.

http://ift.tt/2jv9Tog

0 notes