#indigenous knowledge

Text

In the Willamette Valley of Oregon, the long study of a butterfly once thought extinct has led to a chain reaction of conservation in a long-cultivated region.

The conservation work, along with helping other species, has been so successful that the Fender’s blue butterfly is slated to be downlisted from Endangered to Threatened on the Endangered Species List—only the second time an insect has made such a recovery.

[Note: "the second time" is as of the article publication in November 2022.]

To live out its nectar-drinking existence in the upland prairie ecosystem in northwest Oregon, Fender’s blue relies on the help of other species, including humans, but also ants, and a particular species of lupine.

After Fender’s blue was rediscovered in the 1980s, 50 years after being declared extinct, scientists realized that the net had to be cast wide to ensure its continued survival; work which is now restoring these upland ecosystems to their pre-colonial state, welcoming indigenous knowledge back onto the land, and spreading the Kincaid lupine around the Willamette Valley.

First collected in 1929 [more like "first formally documented by Western scientists"], Fender’s blue disappeared for decades. By the time it was rediscovered only 3,400 or so were estimated to exist, while much of the Willamette Valley that was its home had been turned over to farming on the lowland prairie, and grazing on the slopes and buttes.

Pictured: Female and male Fender’s blue butterflies.

Now its numbers have quadrupled, largely due to a recovery plan enacted by the Fish and Wildlife Service that targeted the revival at scale of Kincaid’s lupine, a perennial flower of equal rarity. Grown en-masse by inmates of correctional facility programs that teach green-thumb skills for when they rejoin society, these finicky flowers have also exploded in numbers.

[Note: Okay, I looked it up, and this is NOT a new kind of shitty greenwashing prison labor. This is in partnership with the Sustainability in Prisons Project, which honestly sounds like pretty good/genuine organization/program to me. These programs specifically offer incarcerated people college credits and professional training/certifications, and many of the courses are written and/or taught by incarcerated individuals, in addition to the substantial mental health benefits (see x, x, x) associated with contact with nature.]

The lupines needed the kind of upland prairie that’s now hard to find in the valley where they once flourished because of the native Kalapuya people’s regular cultural burning of the meadows.

While it sounds counterintuitive to burn a meadow to increase numbers of flowers and butterflies, grasses and forbs [a.k.a. herbs] become too dense in the absence of such disturbances, while their fine soil building eventually creates ideal terrain for woody shrubs, trees, and thus the end of the grassland altogether.

Fender’s blue caterpillars produce a little bit of nectar, which nearby ants eat. This has led over evolutionary time to a co-dependent relationship, where the ants actively protect the caterpillars. High grasses and woody shrubs however prevent the ants from finding the caterpillars, who are then preyed on by other insects.

Now the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde are being welcomed back onto these prairie landscapes to apply their [traditional burning practices], after the FWS discovered that actively managing the grasslands by removing invasive species and keeping the grass short allowed the lupines to flourish.

By restoring the lupines with sweat and fire, the butterflies have returned. There are now more than 10,000 found on the buttes of the Willamette Valley."

-via Good News Network, November 28, 2022

#butterflies#butterfly#endangered species#conservation#ecosystem restoration#ecosystem#ecology#environment#older news but still v relevant!#fire#fire ecology#indigenous#traditional knowledge#indigenous knowledge#lupine#wild flowers#plants#botany#lepidoptera#lepidopterology#entomology#insects#good news#hope

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

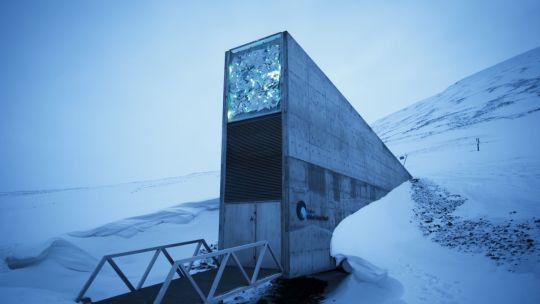

Two men who were instrumental in creating a global seed vault designed to safeguard the world's agricultural diversity will be honoured as the 2024 World Food Prize laureates.

Cary Fowler, the US special envoy for Global Food Security, and Geoffrey Hawtin, an agricultural scientist from the UK and executive board member at the Global Crop Diversity Trust, will be awarded the annual prize and split a $500,000 (€464,000) award. In 2004, Fowler and Hawtin led the effort to build a backup vault of the world's crop seeds in a place where it could be safe from political upheaval and environmental changes.

The facility was built into the side of a mountain on a Norwegian island in the Arctic Circle where temperatures could ensure seeds would be preserved.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault - also known as the 'Doomsday vault' - opened in 2008 and now holds 1.25 million seed samples from nearly every country in the world.

#solarpunk#solar punk#indigenous knowledge#community#reculture#seed vault#svalbard#global food prize#preserving the future

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nature-Culture Divide

Something I have seen a lot of people within the Solarpunk sphere talk about and wonder is: "When did we stop seeing ourself as something outside of nature?" And given that I actually had a module on that (Social Geography, best module I ever had, given we had an anarchist professor!) I thought I could quickly explain this one.

So, the names come, in the end, from Latin and back when those words were considered in Latin, the difference was, that nature was a thing that was innate, while culture had volition behind it. You could change nature into culture by putting work into it.

Something that might surprise you is, that the idea of nature then was never quite big for most of European history. And let me make one thing clear: While we have these ideas also played with in Buddhist culture - especially in East Asia - the way we define it right now is a Western idea.

And that idea... Well, that idea came with colonialism. The thing many do not realize is, how much of the rules and "lines in the sand" that we use in our culture came from colonialisation, came from the desire to make "our" culture different from "theirs". It is shown in the way we eat, in the way we raise children, in the way we view gender and sexuality. And, yes, in the artificial border between nature and culture.

Before I tell you more about this, let me please say here: Yes, this is contradictive. I am aware of it. I am not the one who came up with the contradiction. White settlers did that all on their own.

When the settlers came to America they found a landscape very, very different from what they were used to from Europe. After all, Europe has been changed through human hand for at that point about 1600 years. (And for you Europeans out there: Researching how much forest your local area might have lost through the Romans is always a "fun" thing to do! Because the Romans destroyed a lot of European ancient forests.) In Europe, even at the wildest places, there was usually some evidence of human habitation - but this was not true for the Americas. Not because there were no people there, but rather because the people interacted with the environment very differently.

See, the European idea - while never quite that defined until this point - was really, really based on this thought that nature can be turned into culture. And that this transformation was in fact a good thing to happen. So, when the settlers arrived in the Americas they did not see "culture" there, only "nature" and set out to turn that "nature" into "culture".

Of course, we - modern people living today - do realize that indigenous people had in fact cultures of all sorts and that the actual difference was, that they just did not see that culture as something different from nature, rather than a part of it. Because their culture had not been influenced by Romans. But the settlers back then did not see this or rather did not want to see this. So they "cultured" the land, with the ideas about nature and culture being further formalized at that point.

It kinda stayed like this until the late 19th century, when Madison Grant, the originator of eco fascism came to be influencial. And now he saw something that the settlers until this point were unable to see: The indigenous people do stuff with the nature around them! They change it! For example through controlled burning of forests and things like that.

And this made Madison Grant very angry, because he was very much off the opinion that nature should be "unsoiled" by human hands. So... he made sure that those indigenous people got once more pushed out of the areas they were living, with the same areas being declared natural parks and no longer interfered with by humans (except, of course, all the tourists who destroyed it bit by bit). Leading... To a lot more wild fires.

So, where does this leave us in terms of the culture/nature divide?

Well, the idea has been there since ancient Rome and has very much influenced how much we view nature as its own thing. But within Rome nature was still not quite seen as the opposite of culture - as one could turn into the other. Under the Roman view an abandoned house or a field that was no longer cared for would turn back into nature, while anything could become culture just by interacting with humans.

The modern view really came through colonialism and the way colonialist did not understand (and did not want to understand) indigenous practices. This made people more and more drift towards the understanding of humans being an entirely different thing from nature.

But this is wrong, of course. We are part of nature. We are just animals with fingers and slightly larger brains. And many indigenous cultures understood this. In the end it was the greed of some that made us loose this connection to nature. And that is exactly why we are in this climate change related mess right now.

#solarpunk#history#culture#nature#culture-nature divide#colonialism#anti colonialism#indigenous knowledge#indigenous people#national parks

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous knowledge of palaeontology in Africa

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ecology, the evolutionary sciences and studying indigenous knowledges and lifeways bring you into something that I can only call god.

Knowing the webs of support, entangled giving, the kissing, the shelter under the wing and the world of siblings, all in affection against the great swelling emptiness underpinning. Science only enhances it, knowing the intricacy of the threads, the chains, the fucking MIRACLE that there is any of this. It is a fucking MIRACLE, we live in a dying miracle.

It is so painful, it is bleach in the bloodstream, wreckage and landfills in the all-connecting everything, knowing the cost

I have found something whom's hugeness, whom's offer I could devote myself entirely to. Something worth giving to. The fact of the collapse is incomprehensible in the face of that, beyond pain.

I know it shouldn't arrest me to be able to look at critique and postulation and graphs that depict the collapse, I should be celebrating and grieving and hospicing. I just want to be able to give back in a way that means something. The reality of that is arresting and destroying.

#ecology#climate crisis#indigenous knowledge#the trellis#the web#desire lines#Jeff Vandemeer#Annihilation#Richard Dawson#The Hermit#Ursula K Le Guin#The Farthest Shore#Earthsea

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of Coast Salish “woolly dogs” revealed by ancient genomics and Indigenous Knowledge

81 notes

·

View notes

Link

U.S. officials will work to restore more large bison herds to Native American lands under a Friday order from Interior Secretary Deb Haaland that calls for the government to tap into Indigenous knowledge in its efforts to conserve the burly animals that are an icon of the American West.

Haaland also announced $25 million in federal spending for bison conservation. The money, from last year’s climate bill, will build new herds, transfer more bison from federal to tribal lands and forge new bison management agreements with tribes, officials said.

American bison, also known as buffalo, have bounced back from their near extinction due to commercial hunting in the 1800s. But they remain absent from most of the grasslands they once occupied, and many tribes have struggled to restore their deep historical connections to the animals.

As many as 60 million bison once roamed North America, moving in vast herds that were central to the culture and survival of numerous Native American groups.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

more ruminating, something i want to write down while it’s in my head—

perhaps landback is contentious to non-indigenous people because the concepts of land ownership are different culturally. as i said earlier, western and euro-american view our (humans) relationships to the natural world as inherently destructive. resource hoarding and taking in moderation are not considered. part of this, i think, has to do with the nature of capitalism, that you must take before anyone else can get, to get ahead, and because others are not community but competition. capitalism and cultural christianity go hand and hand; and even leftists and communists who proclaim their freedom from both institutions have often yet to fully decolonize their thinking and truly unlearn their approach to the world. i’ve experienced this, frustratingly, over and over. i’m often spoken over or not listened to when i try to explain this.

but the idea behind landback is not to drive out all others (though i think a lot of us indigenous folks might think about it in our heart of hearts, the irony of driving colonizers back to where they came from), but to allow for us to be stewards of our land once again and for us to have cultural access. somewhere like acadia national park largely bars access to harvesting sweet grass, other medicines, and wild foods because the expectation is that the action of gathering would be destructive. suzanne greenlaw’s work comes to mind. if we look at the euro-american decimation of various species since contact, this concern is easily understood. our relationships with our natural world are culturally different, however, and should be considered seriously. indigenous people should be trusted with the ecological knowledge of homelands.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

36 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Colonialism hasn’t destroyed us entirely, but we’ve got to find our Indigenous knowledges, our Indigenous cultures. That is what ultimately reimagines our humanity, rather than the project of dismantling colonialism.

Actually, I did a lecture about this in London in 2019. I was talking to all these English people and I asked, if you dismantle colonialism in the English university, what will be left? What will actually be left of the university? And everyone looked at me surprised, and I said that I’m asking a serious question: If you dismantle colonialism, will you have anything left? Your world is built entirely on it. But if you ask us, if you dismantle colonialism, what will be left or what will replace it, we know exactly! Indigenous people have this culture, have this knowledge, and have ways of doing things. And it is the same around the world: there are other ways of imagining ourselves. And that is really important when we think about the contribution that Indigenous people and indigeneity can bring.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith in conversation with Bhakti Shringarpure in The Los Angeles Review of Books. Decolonizing Education: A Conversation with Linda Tuhiwai Smith

There are lots of videos of Linda Tuhiwai Smith online. She's quite engaging to listen to. This interview captures that quality. She is a rangatira.

138 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Until as recently as 1970, India was a land with more than 100,000 distinct varieties of rice. Across a diversity of landscapes, soils, and climates, native rice varieties, also called “landraces,” were cultivated by local farmers. And these varieties sprouted rice diversity in hue, aroma, texture, and taste.

But what sets some landraces in a class of their own—monumentally ahead of commercial rice varieties—is their nutrition profiles. This has been proved by the research of Debal Deb, a farmer and agrarian scientist whose studies have been published in numerous peer-reviewed journals and books.

In the mid-1960s, with backing from the U.S. government, India’s agricultural policy introduced fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation facilities, and high-yielding varieties of crops under the moniker of a “Green Revolution” to combat hunger. Instead, it began an epidemic of monocultures and ecological destruction.

In the early 1990s, after realizing that more than 90% of India’s native rice varieties had been replaced by a handful of high-yielding varieties through the Green Revolution, Deb began conserving indigenous varieties of rice. Today, on a modest 1.7-acre farm in Odisha, India, Deb cultivates and shares 1,485 of the 6,000 unique landraces estimated to remain in India.

Deb and collaborators have quantified the vitamin, protein, and mineral content in more than 500 of India’s landraces for the first time, in the lab he founded in 2014, Basudha Laboratory for Conservation. In one extraordinary discovery, the team documented 12 native varieties of rice that contain the fatty acids required for brain development in infants.

“These varieties provide the essential fatty acids and omega-3 fatty acids that are found in mother’s milk but lacking in any formula foods,” Deb says. “So instead of feeding formula foods to undernourished infants, these rice varieties can offer a far more nutritious option...”

Deb’s conservation efforts are not to preserve a record of the past, but to help India revive resilient food systems and crop varieties. His vision is to enable present and future agriculturists to better adapt to climate change...

Deb conserves scores of climate-resilient varieties of rice originally sourced from Indigenous farmers, including 16 drought-tolerant varieties, 20 flood-tolerant varieties, 18 salt-tolerant varieties, and three submergence-tolerant varieties. He shares his varieties freely with hundreds of small farmers for further cultivation, especially those farming in regions prone to these kinds of climate-related calamities. In 2022 alone, Deb has shared his saved seed varieties with more than 1,300 small farmers through direct and indirect seed distribution arrangements in several states of India.

One of these farmers is Shamika Mone. Mone received 24 traditional rice varieties from Deb on behalf of Kerala Organic Farmers Association, along with training on maintaining the purity of the seeds. Now these farmers have expanded their collection, working with other organic farming collectives in the state of Kerala to grow around 250 landraces at two farm sites. While they cultivate most of their varieties for small-scale use and conservation, they also cultivate a few traditional rice varieties for wider production, which yield an average of 1.2 tons per acre compared with the 1 ton per acre of hybrid varieties.

“But that’s only in terms of yield,” Mone says. “We mostly grow these for their nutritional benefits, like higher iron and zinc content, antioxidants, and other trace elements. Some varieties are good for lactating mothers, while some are good for diabetic patients. There are many health benefits.”

These native varieties have proven beneficial in the face of climate change too.

With poor rains in 2016, for example, the traditional folk rice variety Kuruva that Mone had planted turned out to be drought-tolerant and pest-resistant. And in 2018, due to the heavy rains and floods, she lost all crops but one: a folk rice variety called Raktashali that survived underwater for two days.

“They have proven to be lifesavers for us,” Mone says.” -via Yes! Magazine, 12/14/22

#india#rice#indigenous knowledge#farming#agriculture#climate change#climate resilience#sustainable agriculture#traditional knowledge#drought resistance#nutrition#good news#hope

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the heart of the Jilobi Forest, a biodiversity hotspot in Eswatini’s eastern region of Lubombo, the three chiefdoms inhabiting the territory had longstanding disputes, and tensions used to run high.

“Most of the disputes resulted in illegal activities like wood-cutting and livestock theft by outsiders and people from the communities who took advantage of the polarisation.”

In a bid to conserve the Jilobi Forest from repeated encroachment, it became essential for the chiefdoms to reconcile to jointly manage and protect the space.,

“Ultimately, talks were facilitated to help chiefs and communities recognise that the ongoing rivalry was detrimental not only to their collective heritage but also to the precious Jilobi Forest,”

Chiefdoms were receptive to altering course when they knew that the conservation of the forest would be particularly beneficial to their communities. The Joint Management Committee was established in 2021 to help the three chiefdoms jointly manage the resources of Jilobi by coming together to devise a reforestation plan that involves responsible forestry practices such as responsible grazing and avoiding protected areas.

“We were able to sort out our differences,” Chief Maliwa said.

#solarpunk#solar punk#africa#indigenous knowledge#community#restoration#biodiversity#putting nature first#eswatini#swaziland

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solarpunk and colonial thinking

Keeping my Solarpunk rambles up... And today a more serious topic, but I kinda want to talk about it.

Solarpunk has a weird, weird relation with decolonialism, colonialism and indigenous rights and indigenous knowledge. On one hand, Solarpunk loves to reference some indigenous knowledge, if it is handy. One example that comes to mind is different indigenous American forms of agriculture, like the three sisters. On the other hand, though...

I see a lot of white Solarpunks also kinda converting to the entire idea of "the noble savage". Like "OMG, the indigenous people were so in synch with nature" and stuff like that. Things that are super harmful as a main narrative. And also... as soon as indigenous people do something, that white folks do not like, a lot of white solarpunks will instantly go into full colonizer mode. A good example of that is indigenous hunting practices or practices of animal sacrifice.

And, of course, when it comes to land management, white folks - and that includes a lot of solarpunks - will also very quickly think they know better or know what is better. In Finnland there was a wind farm build recently on sacred Sami land. And, like... That's just not okay.

I mean, I am mostly white. (Like, my great grandmother was Chinese, but I have been raised white and do not look Chinese. So... eh.) But I honestly do think, that we can learn quite a few things from different indigenous cultures (and with that I do not only mean the indigenous tribes of north america). But if we learn from them, we cannot just take knowledge that we like and run with it. Cultural exchange should be that. Exchange. Respectful. Not just appropriation of the three things we like.

Also: Watch Andrewism on YouTube. He talks about that a lot.

#solarpunk#indigenous rights#indigenous peoples#indigenous#cultural exchange#land back#indigenous sovereignty#indigenous knowledge

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall-Kimmerer

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love science. But also, I can clearly see how it is the western man’s explanation of explicit indigenous knowledge. ESPECIALLY in agriculture and food systems. Isn’t it quite interesting to think about how regenerative agriculture was THE way of living. We’ve strewn so far from this form of food production that now rich white women with masters degrees and inherited land get to teach others “regenerative agriculture” for profit. It irritates me that our culture (mostly white culture) needs the chemical, biological, physical, scientific proof that something works when oral traditions have been tried and true on this continent for 10,000 years. Is the scientific method a means of distraction so big ag, big pharma, big oil, and big chem can make a profit?

#the circle of capitalism#western science#indigenous knowledge#same language#agriculture#regenerative agriculture#indigenous voices#food systems#native rights#sustainability#fuck capitalism#life#wicked witch#green anarchy#the wicked witch of the east#why does tumblr hate me#big ag#small ag#circular#solarpunk#profit#profit to the people#united we stand

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous communities have sustained and coexisted with their ecosystems for centuries, holding wisdom about local forests and biodiversity. Integrating their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) with technological approaches can enhance the effectiveness of restoration initiatives while ensuring holistic, culturally sensitive, and sustainable solutions.

Organizations like PRISMA in El Salvador and FOCEN in Mexico exemplify this synergy by integrating cutting-edge tools with community needs.

PRISMA's use of satellite data and local knowledge has enabled targeted reforestation efforts, leading to measurable increases in forest cover and biodiversity. Similarly, FOCEN's collaboration with Global Forest Watch has facilitated real-time monitoring of Monarch butterfly habitat, empowering local communities to detect and respond to threats more effectively.

These partnerships demonstrate the transformative potential of combining technology with community-driven conservation initiatives, paving the way for a more collaborative and sustainable future.

By recognizing the value of Traditional Ecological Knowledge and actively seeking collaboration with Indigenous communities, we can leverage the combined strengths of traditional wisdom and technological advancements to create more effective restoration strategies that benefit both the environment and the people who depend on it.

#solarpunk#solarpunk business#solarpunk business models#solar punk#reculture#indigenous knowledge#indigenous technical knowledge#traditional ecological knowledge#TEK#tech#technology#solarpunk AF#indigenous solarpunk

5 notes

·

View notes