#mishima: a life in four chapters

Text

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) // dir. Paul Schrader

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)

921 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yukio Mishima has been trending this week for uh, reasons. He was a world renowned Japanese author and all of his work is overshadowed by his actions on November 25, 1970. You might not want to read more about this guy because he is horrible and disgusting, but he's utterly fascinating and the movie about him is brilliant.

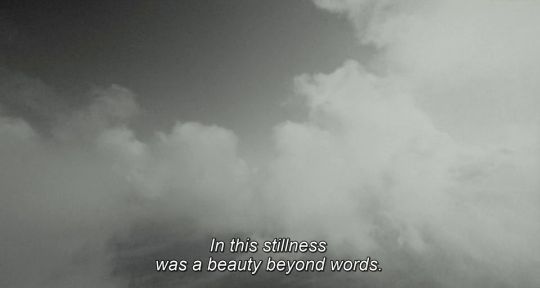

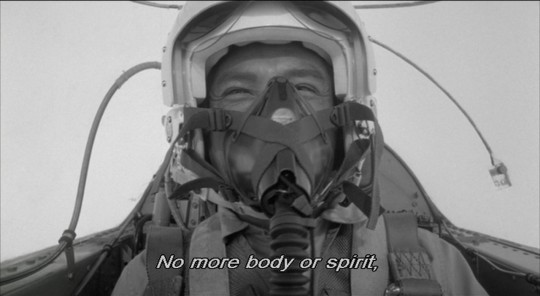

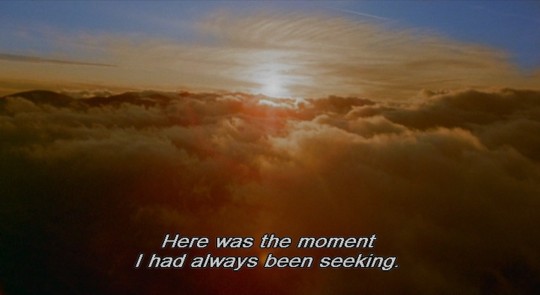

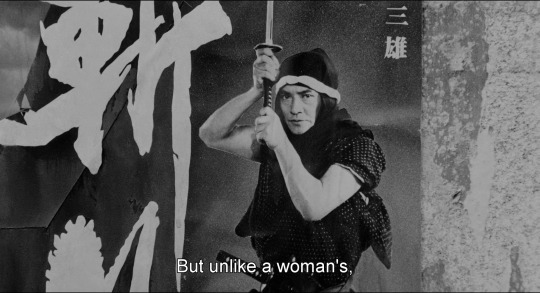

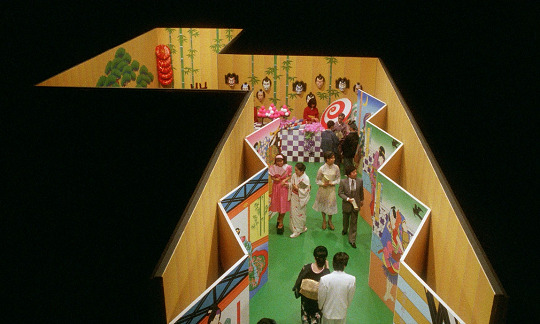

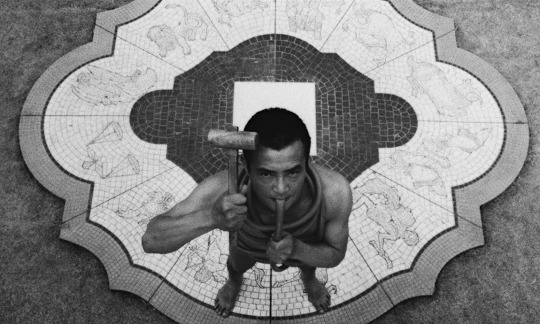

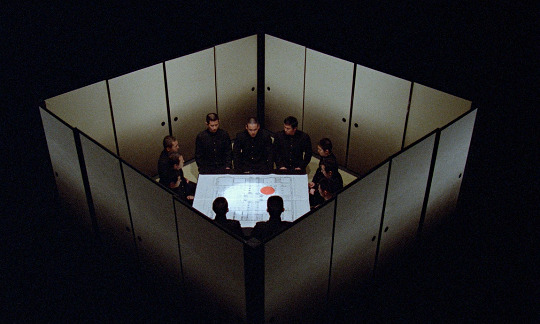

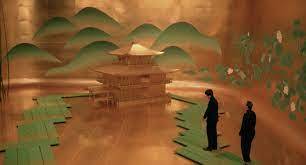

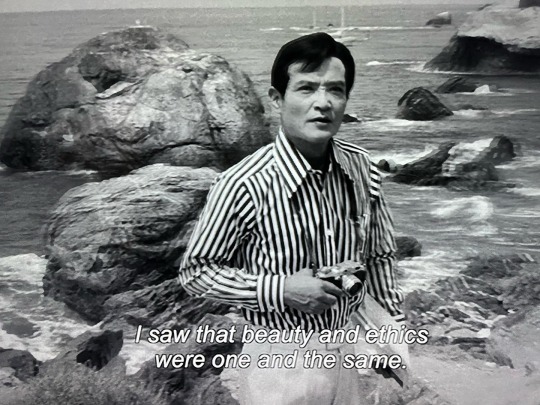

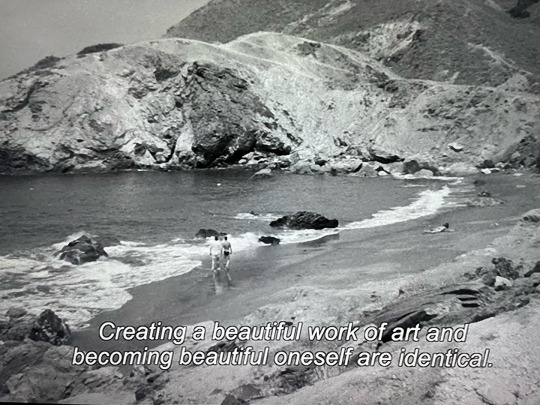

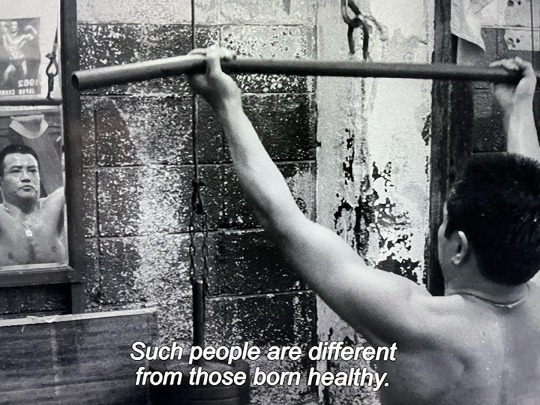

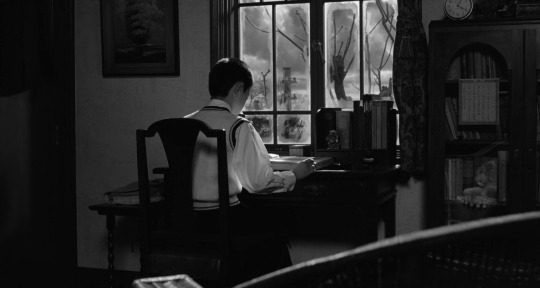

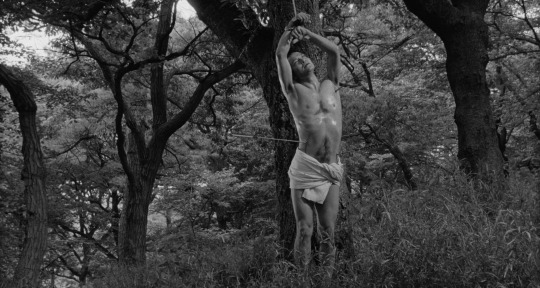

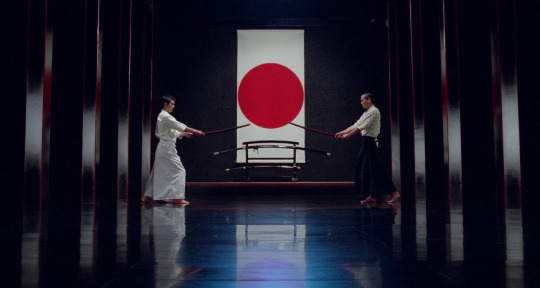

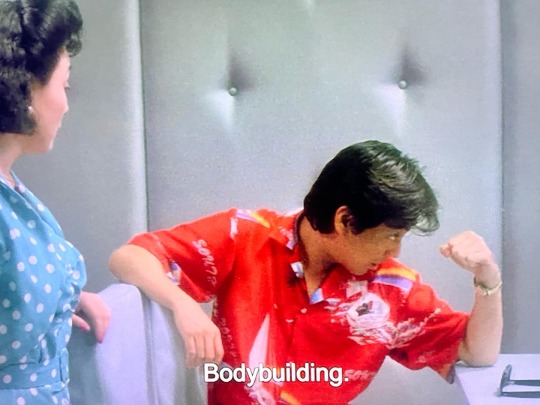

He's a really interesting character, to the point that he sounds fictional. He's gay, obsessed with ritualistic death, a right wing lunatic, led a private militia that was halfway to a cult, and also was a legitimately great author. His life is covered in the film Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters and it's easily the most beautiful film I've seen in my life. Look at the stills I posted above; every frame of this movie looks like that. It's all just a series of beautiful paintings with people living in them.

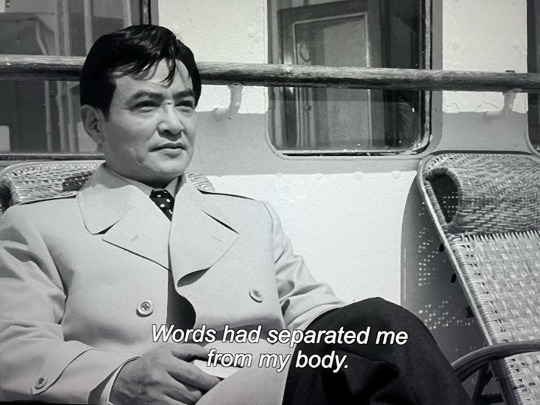

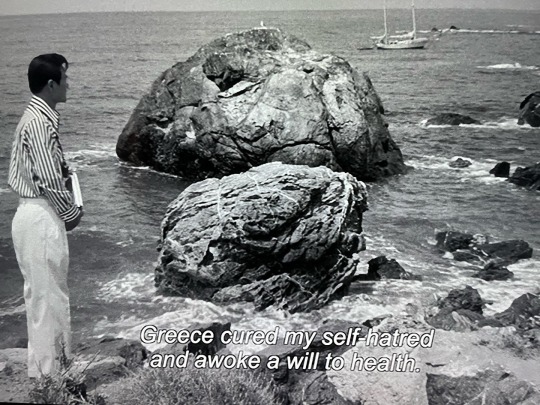

The way the film is structured is that it tells the story of his life in three ways. His past is told in black and white flashbacks with static cameras. This is closer to how a movie from the 50's would look like (specifically ones directed by Yasujirō Ozu). The events of three of his books are told with this beautifully stylized look, with sets that look like stage plays. The events of November 25, 1970 is told in an almost normal fashion, with regular colors and competent camerawork. The past is nostalgic, the present is mundane and only in fantasy can you truly come alive.

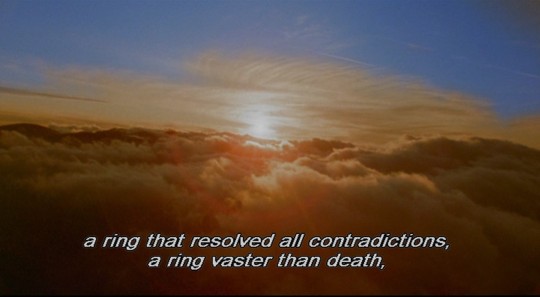

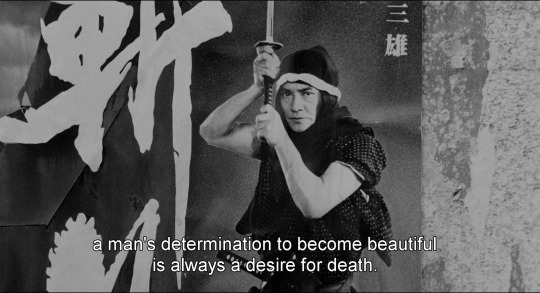

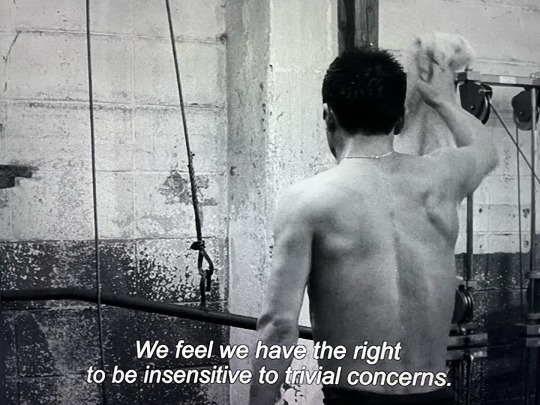

Through this movie we see the ideology of Mishima coming through. His nationalism, his sexual feelings and his thoughts on beauty and death all come together. Death isn't just a violent and tragic end, it is in itself a beautiful act. Beauty is the only true goal of life and creating beauty brings honor. Growing old and ugly is an act of hate; to die at your peak is to give love back to the world. It is therefore treasonous to live long enough to die peacefully. He pities what heaven must look like now; when men died young and beautiful it was paradise, but now it is filled with old men.

This is an objectively insane way to view the world but it is also fascinating. How much of this was what he believed, and how much of it was just begging for attention? In one instance when asked why he moved to the right politically he said "because the left was full". It was a joke answer, but he clearly wanted to be in the spotlight. His shield society was a paramilitary group dedicated to living a virtuous life of beauty, honor and old ideals. It was also a group of good looking, athletic young men led by a (barely) closeted, conservative gay man. So much of his life could have gone differently but also he was pretty much in control the whole time; he was independently wealthy and revered on the world stage. He could do whatever he wanted, and apparently the way his life went *is* what he wanted.

What's special about Mishima, both in the film and in real life, is that he's a smart and eloquent guy. In films the guy with a crazy worldview is someone like Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver or D-Fens from Falling Down. Travis couldn't understand the alienation and loneliness he felt and he couldn't find any healthy solutions. D-Fens was smart enough but not emotionally strong enough to confront his problems or deal with them maturely. These are people that could benefit greatly from therapy (other examples include Joker from Joker, Rupert Pupkin from the King of Comedy, Frank Murdoch from God Bless America, Patrick Bateman from American Psycho, Tyler Durden from Fight Club and so, so many more).

These are either 20 something year olds that are lost in the world, alienated and lonely, or 40 something year olds with a mid life crisis when they realize that everything has fallen apart. People who don't know where to go, or realize it's too late to change things. Travis Bickle had basically no friends, no family, no charisma with women and a lot of rage and anger. D-Fens lost his job, his self respect and was estranged from his ex-wife and daughter. These are people who's lives are shit at best (Patrick Bateman is a bit of a subversion. He is rich and successful, but his life is completely hollow, his relationships are shallow and he personally is very, very pathetic. I need to write about American Psycho later that film is great too.).

Mishima is different. He's smart enough to understand his issues and how to find help. He's got the money and means to do so. He's famous and rich enough that he could basically get away with anything weird or eccentric so long as it was harmless. On the world stage he was a popular author, and at home he led a life of political activism. If he was unhappy he could easily find healthy ways to fix it. His self destruction was the most avoidable of any of them, yet he's the only one that existed in real life. You expect these people to have serious personality flaws and unfixable (or seemingly unfixable) problems, not to be poetic writers that adhere to healthy living and regularly journal about their emotions, while enjoying respect from their peers and fulfillment in their work.

It's a hell of a film. Paul Schrader has not written or directed anything better (he actually wrote Taxi Driver too, so he had some experience with this type of character before) and it stands out as an incredible experience to watch. Like, Mishima's life is public knowledge and you can probably guess how it went, but I've purposefully not said what happened on November 25, 1970 because I don't want to spoil it. It's an event that actually happened but it's better for you to find out via the film than some wikipedia page.

#film#movie#cinema#paul schrader#yukio mishima#mishima: a life in four chapters#taxi driver#martin scorsese#patrick bateman#american psycho#travis bickle#rupert pupkin#the king of comedy#joker#joker (2019)#god bless america#Frank Murdoch#D-Fens#falling down#fight club#tyler durden#Yasujirō Ozu#japanese film#lgbtqia#lgbtq community#lgbtq

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) | dir. Paul Schrader

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985, dir. Paul Schrader)

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

Paul Schrader

USA/Japan, 1985

★★★★

Dude's got issues.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film #360: 'Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters', dir. Paul Schrader, 1985.

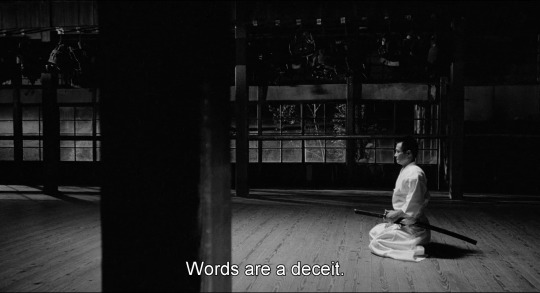

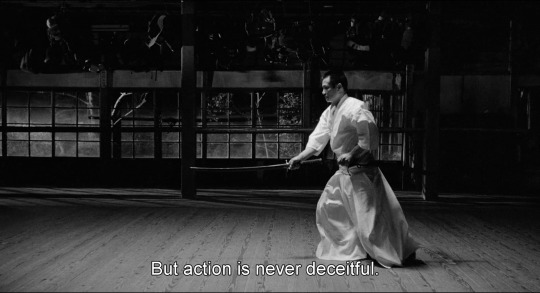

"I realised life consisted of two contradictory elements. One was words, which could change the world. The other was the world itself, which had nothing to do with words."

Considering how psychologically and politically complex the author Yukio Mishima was, it's hardly surprising that Paul Schrader's 1985 film Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters needs to use different visual styles just to keep things straight. Schrader's film illuminates several important periods of the author's life, both through dramatisations of some of Mishima's novels and a portrayal of Mishima's attempted coup in 1970. This strategy was also partly necessary because of how veiled Mishima's life was - in many cases, the only way to access the man is through his novels.

Yukio Mishima was one of Japan's most celebrated writers, publishing dozens of novels, plays, and short stories throughout his life. Many of these works are considered to be at least partially autobiographical. In later life, he became more overtly militaristic and nationalist, leading a platoon of young men who ostensibly were committed to the ideals of bushido, the code of the samurai. Finally, in 1970, he and four of his private guard traveled to a Defense Force base and took the general there hostage, demanding that Mishima be allowed to speak to the assembled troops and encourage them to stage a coup that would lead to the restoration of the Japanese Emperor. When this attempt resulted only in heckling, Mishima and one of his followers committed ritual suicide.

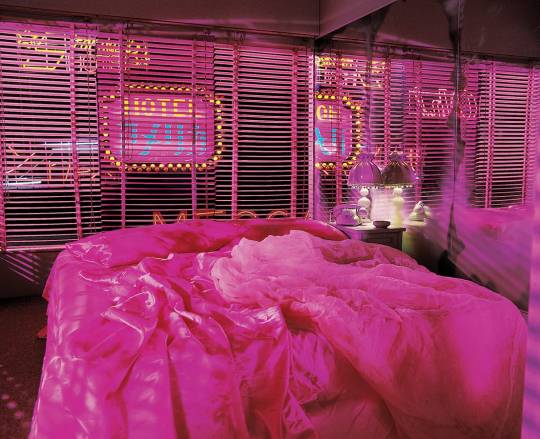

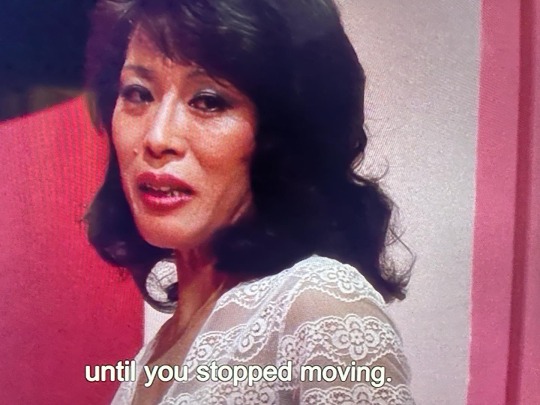

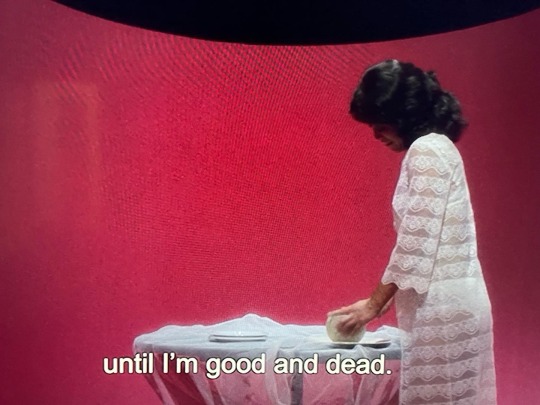

Schrader's film could merely tread the traditional artist biopic path, by filtering everything through a naturalistic depiction of Mishima's life. Instead, he observes that the novels have the capacity to illuminate qualities of the author's life that could otherwise be mundane footnotes. As a result, he strips out almost all biographical detail that can be thematically represented through the lush dramatisations of three of Mishima's novels. Schrader chose sections of three Mishima novels to adapt - The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko's House, and Runaway Horses - but also drew the details of Mishima's early life from the semi-autobiographical novel Confessions of a Mask. In The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, a Zen acolyte is haunted by the beauty of the pavilion, and hopes for its destruction before finally committing to destroying it himself. Kyoko's House explores the story of a young man who enters into an ultimately fatal sadomasochistic relationship with the leader of an organised crime syndicate, while wrestling with his own feelings surrounding his body and his sexuality. Runaway Horses introduces more of Mishima's politically subversive traits - in this novel, young nationalist zealots try and overthrow the government, with the leader eventually committing suicide. Schrader had initially wanted to dramatise a section of another novel, Forbidden Colours, but the rights to the novel were denied by Mishima's widow.

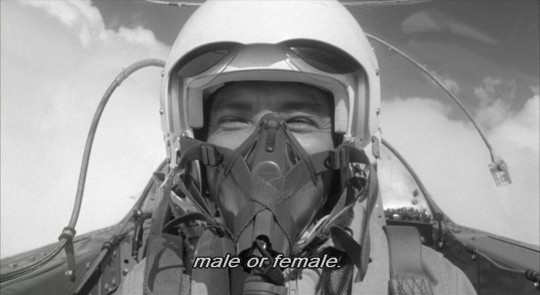

Taken together, the themes of these three novels are almost sufficient to explain the author's life, with its constantly-intertwined themes of violence and sexuality (and a simmering current of misogyny beneath it all), but Schrader also includes some of Mishima's early life in black-and-white footage reminiscent of an Ozu film, and a beat-by-beat coverage of Mishima's final day. To help orient the viewer, the dramatisations take place on artificial sets and the modern-day sequences are filmed in a more naturalistic style. However, this distinction also serves a thematic purpose, fencing off the excesses of Mishima's artistic life. It's almost hard to believe the author of these novels is the same man we see exhorting a platoon of the Defense Force to stage a rebellion. It's only at the very end of the film that Mishima explains how his art and his political beliefs can only be reconciled at the moment of death - to him, all progress is decay, and throughout his life he fights against it, throwing himself into bodybuilding and male-only expressions of camaraderie and political potency. Although his coup fails, it represents the combination of art and death as a force that Mishima sought throughout his life.

And Schrader certainly makes death look pretty. For many years, my only experience of Mishima was a grainy ex-rental VHS tape, which I rescued from the Aro Video clearance bin. I committed the ultimate cinema sin, watching it on a small screen at two in the afternoon without even closing the curtains! Even under those conditions, though, it's the imagery of these dramatisations that has stuck with me. As production designer, Schrader brought in the famed graphic artist Eiko Ishioka. Ishioka's contributions to the film are indelible images that combine 1980s vibrancy with 1950s showroom style, each dramatisation with its own colour scheme and cultural touchstones. Golden Pavilion is an enclosed soundstage with a miniature pavilion, all bedecked in gold and green - what at first seems to be a static set reveals layers of distance and transformation. Kyoko's House moves more into magenta, and most scenes have an establishing shot from a high angle that shows the room adrift in a featureless black space. Runaway Horses uses similar techniques, but the colour palette is in whites and blues, and Ishioka and Schrader use projections to show the sky - a sight we barely see in the film. All of these portrayals are consciously theatrical, a nod to Mishima's experiences in writing drama. Schrader's decision to end each of the dramatisations just before the climax, only to bring each story back at the very end of the film in a dazzling tableau, means that the film is maintaining a complicated balancing act throughout. We're led to believe that the tension before the catharsis is all we'll get out of each story, which makes the images at the end feel like successive punches in the gut. Mizoguchi burns the golden temple to the ground; Osamu and Kiyomi lie dead; Isao kills himself just at the moment of the sunrise. The credits roll over a real-time shot of the orange rising sun, with the thunderous Philip Glass score pulsing throughout (this score, performed in part by the Kronos Quartet, gives the film an otherworldly and sometimes hysterical feeling. I love it).

While Schrader considers Mishima to be the best film he has directed, it has never received an official screening in Japan. A successful boycott of the film was mounted due to its presentation of Mishima as a gay man. This was also the subject of the refused novel Forbidden Colours, which revolves around a gay man who enters a marriage with a woman for financial stability, although it's unclear how closely this resembled Mishima's life - by this point he was an accomplished and wealthy writer. Mishima's widow threatened to file suit against the film, claiming in an interview that her late husband's novels were "overly simplified to distort the meaning to nothing but homosexuality and violence". This criticism is surprising, given the restrained way in which Schrader treats Mishima's sexuality overall. Mishima as shown on the day of his attempted coup has no sexuality at all - his wife and children are alluded to but not shown; his queer affairs appear only in flashback (and given that they're based on Confessions of a Mask, it's not clear if they are meant to be literal events from Mishima's life, or representative elements of Mishima's personality). While we don't know for sure how Mishima identified, he was certainly queer to a significant extent, and it seems that Mishima's queer identity was irreconcilable with the image of the masculine literary lion. Schrader's film, perhaps deliberately, keeps these two subjects in tension. The excerpt from Kyoko's House is the most explicitly queer of the three novels, but its content is still coded. While in this section of the film Osama expresses a desire to cross the boundaries of gender, this is still quarantined within an outwardly heterosexual pairing.

This restraint takes on a physical form within Schrader's film. The vivid and sumptuous sets where queerness is allowed to exist in all its camp glory are also closed boxes, drawing explicit boundaries between the world of emotion and the world of political reality. Schrader treats the three novels as partially autobiographical, but this raises an interesting question, I think: were we meant to know this, to see this, to assume this about the man himself? Did Mishima deliberately intend for his novels to reflect aspects of himself and his personality? Or were these novels a way of distancing and isolating his desires, both for an expansive queer expression and a radical and violent rage? If it is the latter, then Schrader's film has broken down these walls and brought Mishima's complicated identity into full view. Whether you know a lot about Yukio Mishima or are just being introduced, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is the most arresting artist biopic ever committed to film, sumptuous and iconoclastic at the same time.

#1001 movies#genuinely good films#paul schrader#mishima: a life in four chapters#mishima#best of the list

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, Paul Schrader, 1985.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is there a name for the movie genre where a weird pathetic guy just struggles with basic human relationships to the point that he causes a tragedy.

#cinema#movie#film#Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters#The Conversation#8&1/2#Bad Lieutenant#Taxi Driver#King of Comedy#Joker#The Fan#Robert DeNiro is the last four#he really likes making these huh

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)

#1980s#actor ken ogata#dir paul schrader#dp john bailey#cat biography#cat melodrama#american#japanese#pink#magenta#hand#hands#two faces#mirror#sweat#pillow#submission#teeth#mishima: a life in four chapters#mishima: a life in four chapters 1985#mishima 1985#mishima#mishima a life in four chapters#mishima a life in four chapters 1985

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Philip Glass - Mishima/Closing

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)

#Philip Glass#Mishima/Closing#Mishima Closing#Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters#soundtrack#films#music#Kronos Quartet

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, Paul Schrader, 1985

2 notes

·

View notes