#industrial revolution

Text

Mill ruins from 1786

#mine#nature#england#countryside#photography#ruins#mill#architecture#history#industrial revolution#rural#nature photography#buildings#river#waterfall#plants#stream

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Me explaining, once more, that being interested in a particular historical figure or era does NOT necessarily equate to supporting it ‼️ Creators shouldn’t have to make a piece of work “clean” just because some readers may get uncomfortable. If anything, we should be promoting the exploration of uncomfortable topics- proper research and portrayal should be praised. Bring back historical and media literacy.

479 notes

·

View notes

Text

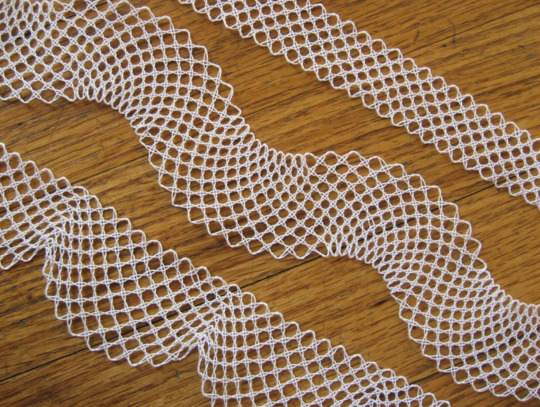

I don't understand how lace is made, but looking at the bobbins and pins and patterns … listen buddy I know math when I see it. This is A Math Thing. Obviously.

Right away I want to know:

Can I encode information in lace?

How much of an expert must one be to make your own patterns?

What about the creation of surfaces?

Knitting is more accessible, and people have been exploring math with knitting forever.

But what possibilities does lace offer?

What is the theory of lace?

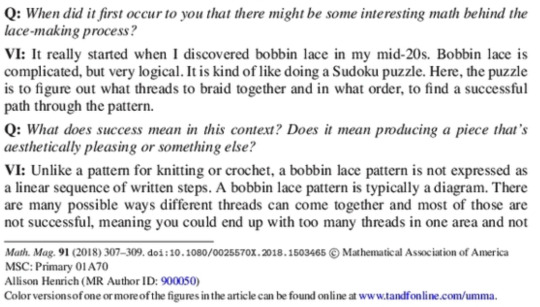

An excerpt from Mathematics Magazine

Vol. 91, No. 4 (October 2018), pp. 307-309

Shows I'm hardly the first person to muse about this. Need to get my hands on the rest of this article, obviously.

#crafts#crafting#making#lace#lacemaking#knitting#mathematics#topology#geometry#bobbin lace#tatted lace#tatting#complexity#patterns#industrial revolution

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

An innovation that propelled Britain to become the world’s leading iron exporter during the Industrial Revolution was appropriated from an 18th-century Jamaican foundry, historical records suggest.

The Cort process, which allowed wrought iron to be mass-produced from scrap iron for the first time, has long been attributed to the British financier turned ironmaster Henry Cort. It helped launch Britain as an economic superpower and transformed the face of the country with “iron palaces”, including Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens’ Temperate House and the arches at St Pancras train station.

Now, an analysis of correspondence, shipping records and contemporary newspaper reports reveals the innovation was first developed by 76 black Jamaican metallurgists at an ironworks near Morant Bay, Jamaica. Many of these metalworkers were enslaved people trafficked from west and central Africa, which had thriving iron-working industries at the time.

Dr Jenny Bulstrode, a lecturer in history of science and technology at University College London (UCL) and author of the paper, said: “This innovation kicks off Britain as a major iron producer and … was one of the most important innovations in the making of the modern world.”

The technique was patented by Cort in the 1780s and he is widely credited as the inventor, with the Times lauding him as “father of the iron trade” after his death. The latest research presents a different narrative, suggesting Cort shipped his machinery – and the fully fledged innovation – to Portsmouth from a Jamaican foundry that was forcibly shut down.

[...]

The paper, published in the journal History and Technology, traces how Cort learned of the Jamaican ironworks from a visiting cousin, a West Indies ship’s master who regularly transported “prizes” – vessels, cargo and equipment seized through military action – from Jamaica to England. Just months later, the British government placed Jamaica under military law and ordered the ironworks to be destroyed, claiming it could be used by rebels to convert scrap metal into weapons to overthrow colonial rule.

“The story here is Britain closing down, through military force, competition,” said Bulstrode.

The machinery was acquired by Cort and shipped to Portsmouth, where he patented the innovation. Five years later, Cort was discovered to have embezzled vast sums from navy wages and the patents were confiscated and made public, allowing widespread adoption in British ironworks.

Bulstrode hopes to challenge existing narratives of innovation. “If you ask people about the model of an innovator, they think of Elon Musk or some old white guy in a lab coat,” she said. “They don’t think of black people, enslaved, in Jamaica in the 18th century.”

847 notes

·

View notes

Text

“By 1900 child mortality was already declining—not because of anything the medical profession had accomplished, but because of general improvements in sanitation and nutrition. Meanwhile the birthrate had dropped to an average of about three and a half; women expected each baby to live and were already taking measures to prevent more than the desired number of pregnancies. From a strictly biological standpoint then, children were beginning to come into their own.

Economic changes too pushed the child into sudden prominence at the turn of the century. Those fabled, pre-industrial children who were "seen, but not heard," were, most of the time, hard at work—weeding, sewing, fetching water and kindling, feeding the animals, watching the baby. Today, a four-year-old who can tie his or her own shoes is impressive. In colonial times, four-year-old girls knitted stockings and mittens and could produce intricate embroidery; at age six they spun wool. A good, industrious little girl was called "Mrs." instead of "Miss" in appreciation of her contribution to the family economy: she was not, strictly speaking, a child.

But when production left the houschold, sweeping away the dozens of chores which had filled the child's day, childhood began to stand out as a distinct and fascinating phase of life. It was as if the late Victorian imagination, still unsettled by Darwin's apes, suddenly looked down and discovered, right at knee-level, the evolutionary missing link. Here was the pristine innocence which adult men romanticized, and of course, here, in miniature, was the future which today's adult men could not hope to enter in person. In the child lay the key to the control of human evolution. Its habits, its pastimes, its companions were no longer trivial matters, but issues of gravest importance to the entire species.

This sudden fascination with the child came at a time in American history when child abuse—in the most literal and physical sense—was becoming an institutional feature of the expanding industrial economy. Near the turn of the century, an estimated 2,250,000 American children under fifteen were full-time laborers—in coal mines, glass factories, textile mills, canning factories, in the cigar industry, and in the homes of the wealthy—in short, wherever cheap and docile labor could be used. There can be no comparison between the conditions of work for a farm child (who was also in most cases a beloved family member) and the conditions of work for industrial child laborers. Four-year-olds worked sixteen-hour days sorting beads or rolling cigars in New York City tenements; five-year-old girls worked the night shift in southern cotton mills.

So long as enough girls can be kept working, and only a few of them faint, the mills are kept going; but when faintings are so many and so frequent that it does not pay to keep going, the mills are closed.

These children grew up hunched and rickety, sometimes blinded by fine work or the intense heat of furnaces, lungs ruined by coal dust or cotton dust—when they grew up at all. Not for them the "century of the child," or childhood in any form:

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out

And see the men at play.

Child labor had its ideological defenders: educational philosophers who extolled the lessons of factory discipline, the Catholic hierarchy which argued that it was a father's patriarchal right to dispose of his children's labor, and of course the mill owners themselves. But for the reform-oriented, middle-class citizen the spectacle of machines tearing at baby flesh, of factories sucking in files of hunched-over children each morning, inspired not only public indignation, but a kind of personal horror. Here was the ultimate "rationalization" contained in the logic of the Market: all members of the family reduced alike to wage slavery, all human relations, including the most ancient and intimate, dissolved in the cash nexus. Who could refute the logic of it? There was no rationale (within the terms of the Market) for supporting idle, dependent children. There were no ties of economic self-interest to preserve the family. Child labor represented a long step toward that ultimate "anti-utopia" which always seemed to be germinating in capitalist development: a world engorged by the Market, a world without love.”

-Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women

526 notes

·

View notes

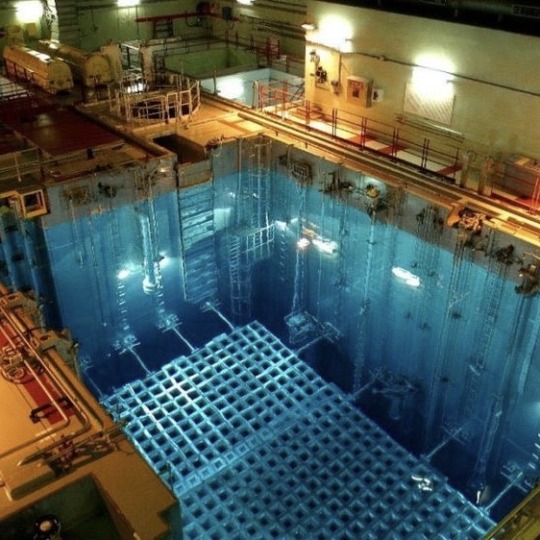

Photo

The spread of the Industrial Revolution through Europe in the 19th century

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legend of Korra: The Industrial Revolution and its Consequences

#legend of korra#Korra#industrial revolution#atla aang#atla#avatar the last airbender#lok#the avatar#avatar aang#avatar korra#avatar kyoshi#aang#asami sato#mako#bolin#uncle iroh

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the right amount of Lou Reed and Terry Pratchett can heal any lost and broken soul

#Is neil gaiman patient zero of this theory of mine? Maybe#lou reed#discworld#terry pratchett#neil gaiman#sir terry pratchett#the velvet underground#witches#city watch#wizards#death discworld#industrial revolution#belphegor luna

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

#whaling#whales#machines#industrial revolution#moby dick#1800s#bar charts#coolness graphed#graphs#charts#webcomics#work#industry#blubber#history

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barcelona, like other cities in urban Europe, was once a major industrial city full of factories. As economy has changed, nowadays most of those factories of the industrial revolution don’t exist anymore. When the city grew, they demolished the factories to make space for modern buildings, but often they have kept the chimneys as a reminder of the past. When you find a lone chimney among modern buildings, it’s the only remains of where there was once a factory.

Photo taken in Barcelona (Catalonia) by David Cardelús on Twitter.

#barcelona#catalunya#fotografia#chimney#industrial revolution#urban#urban photography#city#cities#late modern history#cityscape#photography#europe#archaeology#history#industrial heritage#urban photoshoot#travel photography

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

#history#ancient history#modern history#medieval#medieval history#renaissance#industrial#industrial revolution#WW1#WW2#Cold War#modern#Q n A#poll#random polls

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon’s decree in 1810: First regulation limiting pollution in French history

Source: Décret impérial du 15/10/1810

This comes after the creation of the Public Hygiene and Health Council of the City of Paris on 6 July 1802, and each department getting its own Health Council.

In addition, the ordinance of the Prefect of Police on 12 February 1806 concerning preliminary investigations then authorization necessary for factories, workshops and laboratories producing polluting or dangerous products.

According to Éloi Laurent (Towards Social-Ecological Well-Being):

“The first laws regulating French industrial establishments and in particular the imperial decree of October 15, 1810 was the first legislation in the world regulating pollution (it was extended by the law of December 19, 1917).”

Below is an English translation of the 1810 decree.

————-

Imperial decree of 10/15/1810 relating to factories and workshops that emit an unhealthy or inconvenient odor.

NAPOLEON, Emperor of the French, King of Italy, Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine, Mediator of the Swiss Confederation;

On the report of our Minister of the Interior;

Considering the complaints brought by various individuals against factories and workshops whose operation gives rise to unhealthy or inconvenient exhalations;

The report made on these establishments by the chemistry section of the physical and mathematical sciences class of the Institute;

Our Council of State heard;

We HAVE DECREED and DECREE the following:

Article 1 of the decree of 15 October 1810

As of the publication of this decree, factories and workshops which emit an unhealthy or inconvenient odor may not be formed without permission from the administrative authority: these establishments will be divided into three classes.

The first will include those who must be located away from private homes.

The second will include factories and workshops whose distance from homes is not strictly necessary, but which should only be set up once it is certain that the operations carried out there will not inconvenience or cause damage to neighboring homeowners.

In the third class will be establishments which can remain near homes without inconvenience, but must remain subject to surveillance by the police.

Article 2 of the decree of 15 October 1810

The necessary permission for the formation of factories and workshops included in the first class will be granted, with the following formalities, by a decree issued by our Council of State.

Permission for the operation of establishments in the second class will be granted by the prefects, on the advice of the sub-prefects.

Permissions for the operation of establishments in the last class will be issued by sub-prefects, who will first obtain the opinion of the mayors.

Article 3 of the decree of 15 October 1810

Permission for first class plants and factories will only be granted subject to the following formalities:

The request for authorization will be presented to the prefect, and posted, by his order, in all communes within a five kilometer radius.

Within this period, any individual will be allowed to present grounds of opposition.

The mayors of the communes will have the same right.

Article 4 of the decree of 15 October 1810

If there is opposition, the Prefecture Council will weigh in, with the exception of a decision by the Council of State.

Article 5 of the decree of 15 October 1810

If there is no opposition, permission will be granted, if necessary, on the advice of the prefect and the report of our Minister of the Interior.

Article 6 of the decree of 15 October 1810

If it concerns a soude[*] factory, or if the factory is to be established within the customs area, our Director of Customs will be consulted.

Article 7 of the decree of 15 October 1810

Authorization to form factories and workshops in the second class will only be granted after the following formalities have been completed.

The entrepreneur will first send his request to the sub-prefect of his arrondissement, who will forward it to the mayor of the commune in which the establishment is to be formed; by instructing him to carry out a de commodo et incommodo[**] enquiry. Once this is completed, the sub-prefect will issue a decree which he will forward to the prefect. The prefect will make the decision, unless any interested parties appeal to our Council of State.

If there is opposition, it will be decided by the Prefecture Council, except for an appeal to the Council of State.

Article 8 of the decree of 15 October 1810

Factories or establishments in the third class can only be formed with the permission of the Prefect of Police, in Paris, and the mayor in other towns.

If complaints arise against the decision taken by the Prefect of Police or the mayors, on a request to form a factory or workshop included in the third class, they will be judged by the Prefecture Council.

Article 9 of the decree of 15 October 1810

The local authority will indicate the place where the factories or workshops included in the first class may be established, and will specify its distance from private dwellings. Any individual who carries out construction in the vicinity of these factories and workshops after their establishment has been authorized will no longer be allowed to request their removal.

Article 10 of the decree of 15 October 1810

Establishments that emit an unhealthy or inconvenient odor will be divided into three classes in accordance with the table appended to this imperial decree. It will serve as a rule whenever it comes to deciding on requests for the formation of these establishments.

Article 11 of the decree of 15 October 1810

The provisions of this decree will not have retroactive effect: consequently, all establishments currently in operation will continue to operate freely, with the exception of any damages to which contractors may be liable in the event of damage to the property of their neighbors; such damages will be settled by the courts.

Article 12 of the decree of 15 October 1810

However, in the event of serious inconvenience for public health, culture, or the general interest, first-class factories and workshops causing such inconvenience may be suppressed by virtue of a decree issued by our Council of State, after having heard the local police, taken the opinion of the prefects and received the defense of the manufacturers.

Article 13 of the decree of 15 October 1810

Establishments maintained under article 11 will cease to enjoy this benefit as soon as they are transferred to another location, or if there is a six-month interruption in their work. In either case, they will fall into the category of establishments to be formed, and they will not be able to resume activity until they have obtained a new permit, if necessary.

Article 14 of the decree of 15 October 1810

Our Ministers of the Interior and the General Police are each responsible for the execution of the present decree, which will be published in the Bulletin of Laws.

NAPOLEON

By the Emperor:

Minister Secretary of State,

H. B. DUKE OF BASSANO

——————

My notes:

Attached to this decree is an appendix with

“nomenclature of factories, establishments and workshops emitting an unhealthy or inconvenient odor, which may not be set up without permission from the Administrative Authority.”

Some of the substances listed can be translated and some cannot. I recommend going to the link at the top of this post to check it out if interested.

[*] Soude definition

[**] De commodo et incommodo definition

Public Hygiene and Health Council of the City of Paris is a translation of Conseil d'hygiène publique et de salubrité de la Ville de Paris

An additional source on this legislation: Fondation Napoléon

#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#pollution#environment#environmental regulations#climate#industrial revolution#industrial#Napoleon’s reforms#napoleonic reforms#reforms#history#france#imperial decree#regulations#french revolution#ecology

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not the original Anon but I think the rise of Europe meant that after the Black Death Europe underwent the Renaissance and Industrial Revolution and became a global power so did the former create the conditions for the others?

I sort of thought that was what anon was talking about, so I might as well answer it here. TLDR: there's a big debate about this, and historians have not come to a consensus.

When I was an undergraduate, I took a course on the origins of capitalism by the late Professor J.W Smit, and one of his lectures was on the theory that the Black Death created the preconditions for the Commercial and then Industrial Revolutions, by essentially killing about 30-50% of the population while leaving their property (land, livestock, buildings, improvements, liquid capital, etc.) intact - thus creating a much higher rate of capital-per-capita that could then be invested in more capital-intensive, higher value-added industries.

On the other hand, a lot of medievalists who study the High Middle Ages argue that the period from 1000-1300 saw substantial economic growth due to population growth that enabled both an expansion of agricultural production and the first wave of post-Roman urbanization, and that the Black Death was an enormous setback for huge swathes of Europe who would not recover their pre-Plague levels of population and economic production until the 19th century.

While this might sound like squishy centrism, I think the reason that there is no consensus is that both sides are simultaneously right and wrong. It is true that the Black Death made profound socio-economic change possible by disrupting serfdom, raising wages, and deepening capital pools. It is simultaneously true that the Black Death also created a downward spiral of lower population leading to lower production leading to lower population, which could cripple entire regions for centuries if they were unable to adapt to changing circumstances.

#history#historical analysis#black death#european history#commercial revolution#industrial revolution#economic history#demographic history#medievalism#medieval economics#economic development

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had it not been for the steady stream of cheap raw cotton flowing out of the New World (which supplied nearly three-quarters of Britain’s imports of raw cotton), the British cotton industry would have never been able to play such a central role in Britain’s industrialisation. As David Washbrook notes, ‘[c]otton was exceptionally well-placed to lead the move towards mechanization: but favourably placed precisely because its raw material came from abroad’. That the British were able to outsource the production of raw cotton to the Americas – where the costs of production and labour in particular were considerably lower – was central to their industrial takeoff in the 18th century. Through the institution of the slave plantation in the colonies, capitalists were able to significantly reduce the costs of constant capital in the form of raw materials. Without this key input, it is highly unlikely British manufactures could have overcome the formidable competition from Indian cotton textiles, which even in the mid-18th century still held a leading position in world markets. The ‘workshop of the world’ was thus built on the foundations of plantation slavery.

Alexander Anievas and Kerem Nişancıoğlu, How the West Came to Rule: The Geopolitical Origins of Capitalism

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

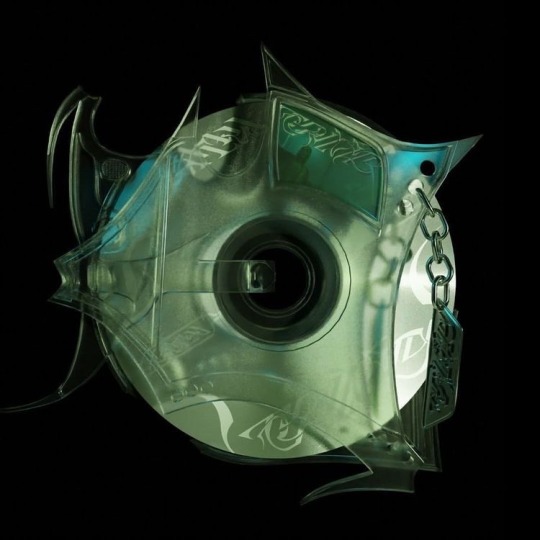

the industrial revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race

#carrd resources#carrd icons#cyber icons#carrd cyber#cyber carrd#cyber moodboard#carrd moodboard#green moodboard#future#weirdcore moodboard#liminal spaces#liminal tw#weirdcore#odd moodboard#messy moodboard#carrd stuff#messy layouts#dreamcore#technology#industrial revolution

621 notes

·

View notes

Text

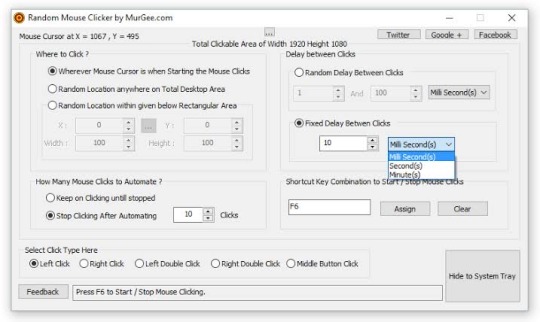

i am working on industrial scale clicker training which will involve using autoclickers with “random click rate” functionality. this technology will revolutionize the petplay industry

22 notes

·

View notes